If you're a patient reading this article while waiting for a doctor or nurse to show up, take a moment to appreciate the irony.

You may be sitting in an exam room by yourself, but you're hardly alone. According to the 2015 Vitals Wait Time Report, U.S. patients spend an average of 19.25 minutes waiting to be seen by a practitioner.

It may be cold comfort, but your wait is really not the fault of the doctor or nurse you've come to see. And, like it or not, it's not even the fault of Obamacare or the influx of 30 million new patients into the healthcare system. Your wait is largely the consequence of a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-scrubs approach to patient scheduling that healthcare practitioners have been using for years.

Creating a schedule that sequences appointment slots optimally turns out to be an extremely complex challenge. When you factor in real-world goals and constraints—such as number patients to be seen, number of exam rooms, number of practitioners available, different visit durations, the number of available appointment start times and more—the actual number of ways that a scheduler could sequence appointments is mind-boggling. Even a practice seeing only 70 patients in a day might have 1050, 1060 even 10100 possible schedule sequence permutations—for a single day. The majority of these schedule sequences will not be optimized to minimize wait times or to optimize resource utilization, of course, but the sheer number of possible permutations means that there's virtually no chance that a scheduler will stumble upon the optimal sequence of appointments serendipitously. So, we wait.

Quantifying the Pressure

There's serious pressure in the healthcare system to adopt a new approach to scheduling. Consider the following 13 data points if you have any doubt:

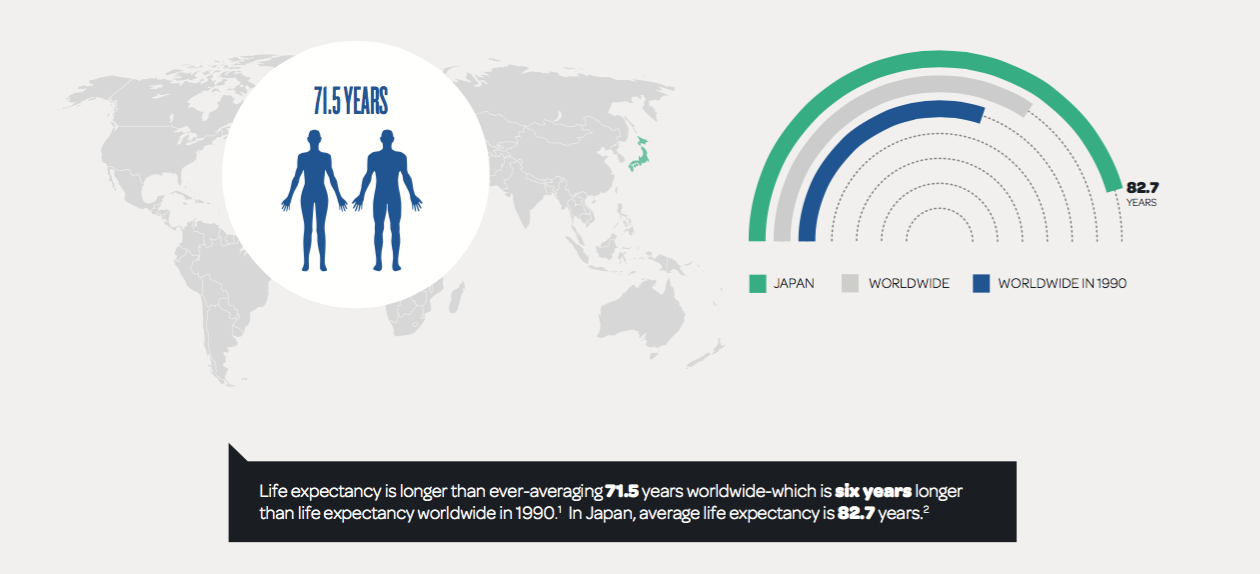

- Life expectancy is longer than ever—averaging 71.5 years worldwide—which is six years longer than life expectancy worldwide in 1990. In Japan, average life expectancy is 82.7 years.

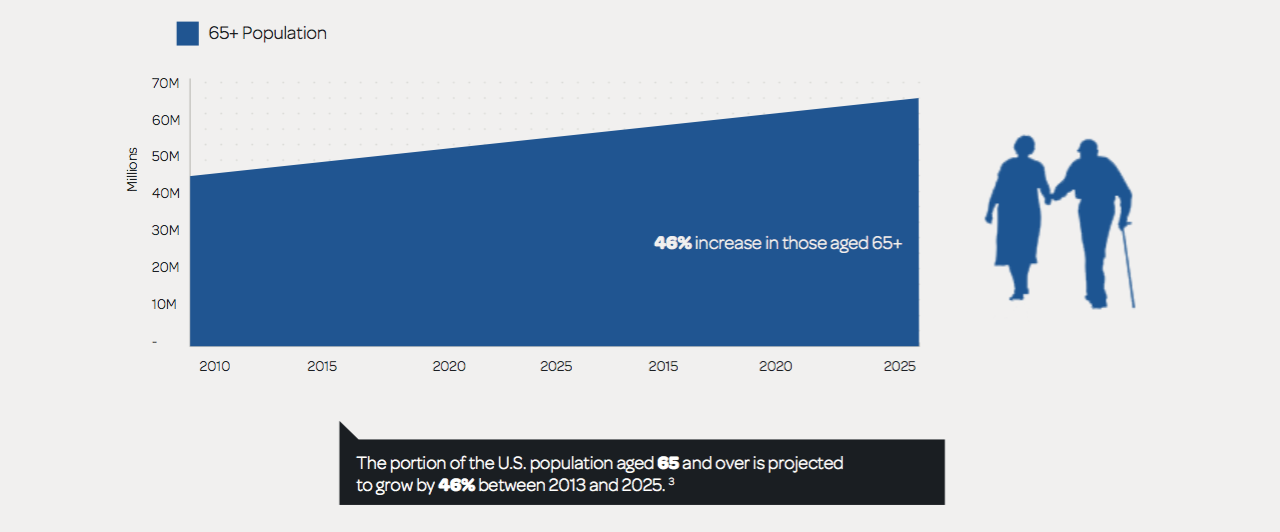

2. The portion of the U.S. population aged 65 and over is projected to grow by 46% between 2013 and 2025.

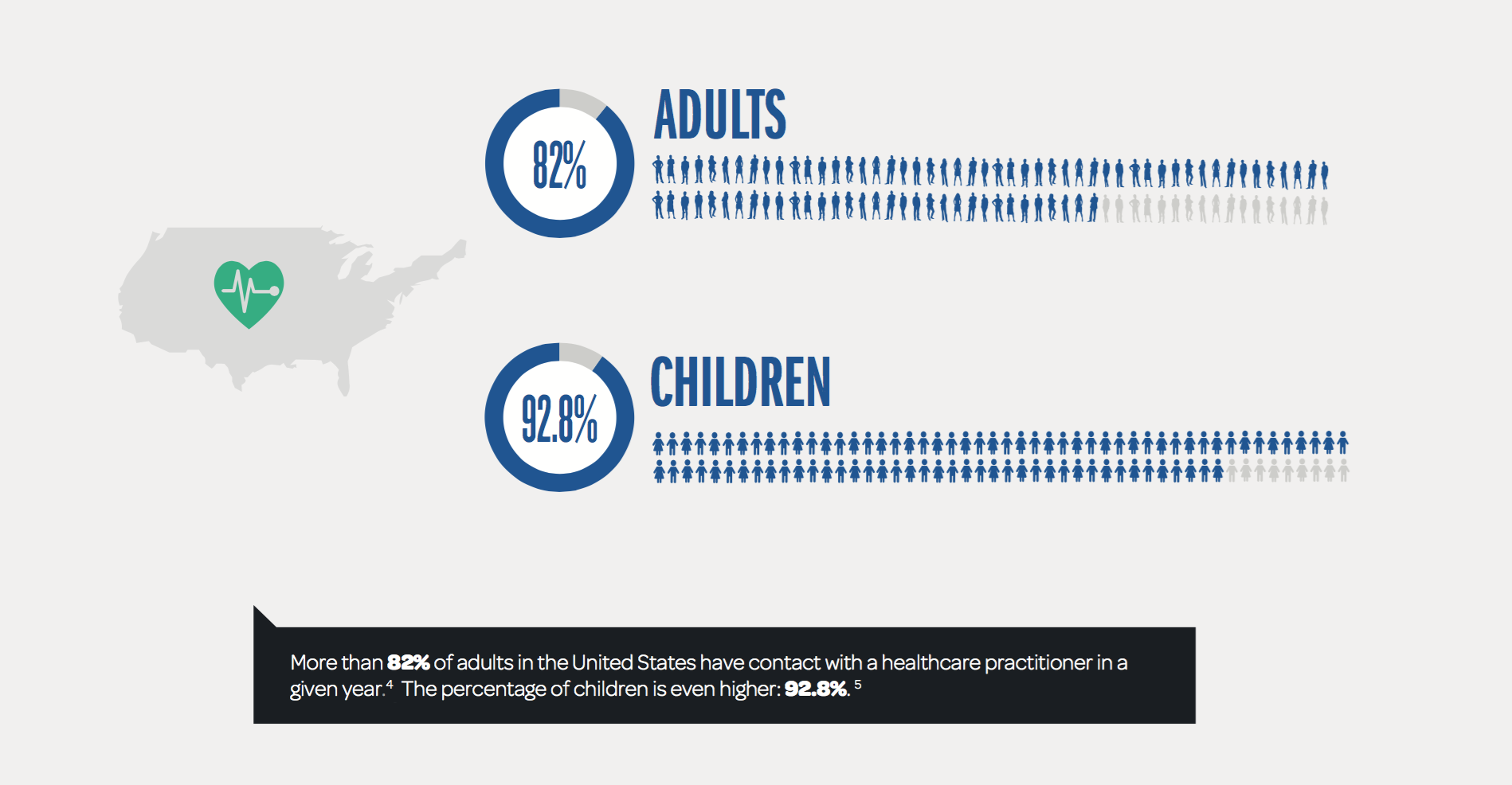

3. More than 82% of adults in the United States have contact with a healthcare practitioner in a given year. The percentage of children is even higher: 92.8%.

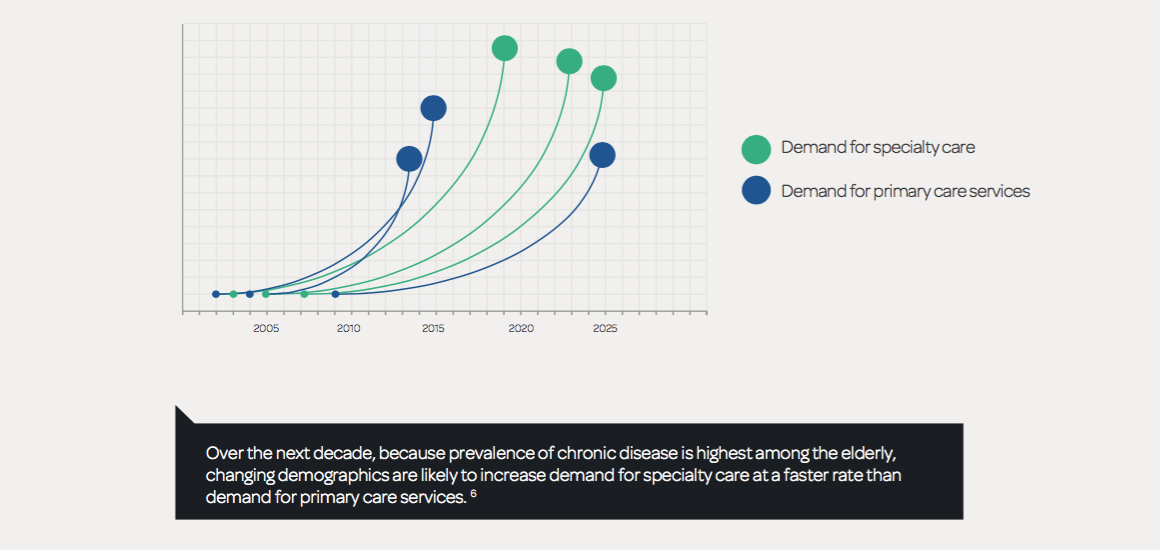

4. Over the next decade, because prevalence of chronic disease is highest among the elderly, changing demographics are likely to increase demand for specialty care at a faster rate than demand for primary care services.

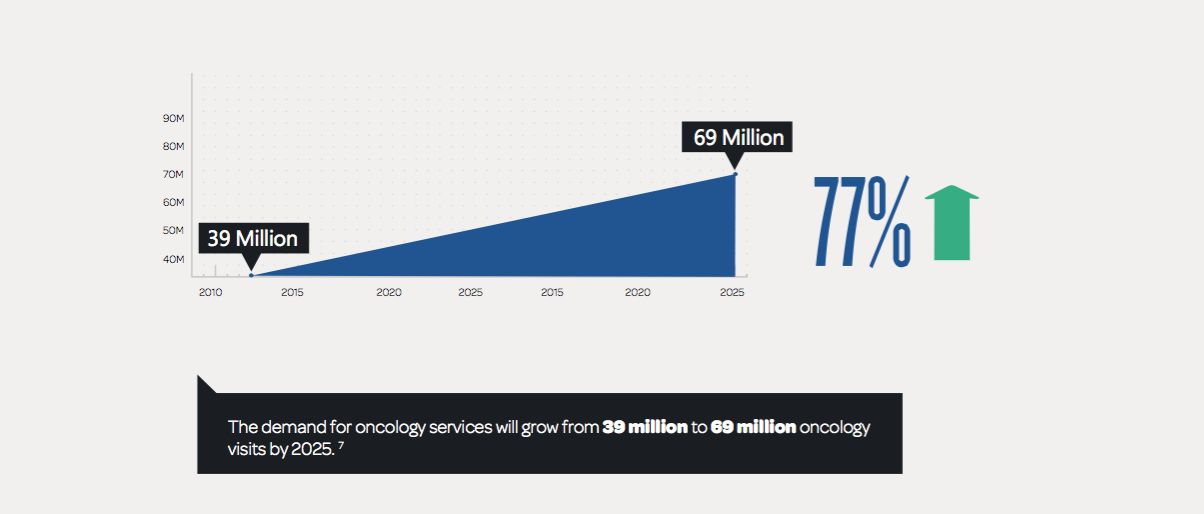

5. The demand for oncology services will grow from 39 million to 69 million oncology visits by 2025.

6. It is estimated that the U.S will face a shortfall of 90,000 physicians by 2025.

Wait, wait, there's more...

Without a way to optimize scheduling, more patients means more waiting—and the amount of time we already spend waiting is a problem:

7. A 2015 survey by Vitals.com found that U.S. patients spend an average of 19.25 minutes waiting to see their doctor.

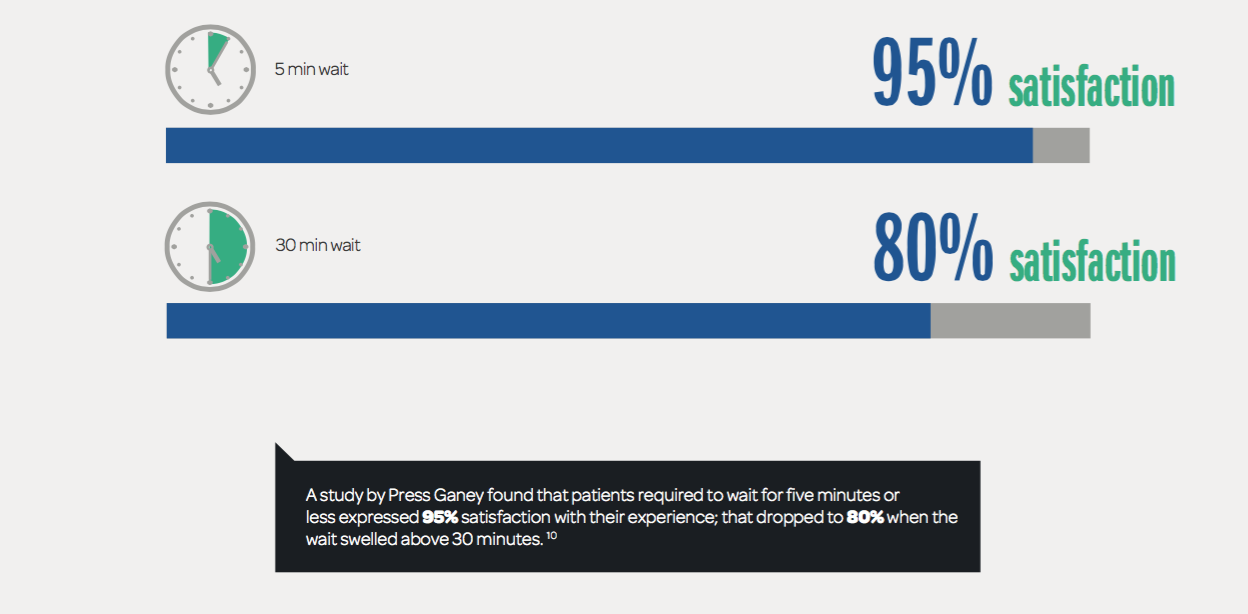

8. A study by Press Ganey found that patients required to wait for five minutes or less expressed 95% satisfaction with their experience; that dropped to 80% when the wait swelled above 30 minutes.

9. Altogether, physician offices, hospital outpatient centers, and emergency departments handle more than 1.25 billion visits per year in the U.S. Of these, 10.4% are hospital emergency room visits; the remaining 89.6%—or 1.12 billion visits—are to physicians' offices, hospital outpatient centers and other locations where visits are likely to be scheduled.

10. So, do the math: If each scheduled visit involves a 19.25 minute wait, the total time spent waiting to see a practitioner amounts to more than 21.5 billion minutes. Let's convert that into something a bit more accessible: Each year, American patients spend the equivalent of just over 41,000 years waiting for their practitioner to show up.

Caregivers have reason to care, too

Dissatisfaction arising from prolonged waits is not just a problem for patients. When patient schedules are poorly designed, healthcare providers suffer and costly assets go underutilized.

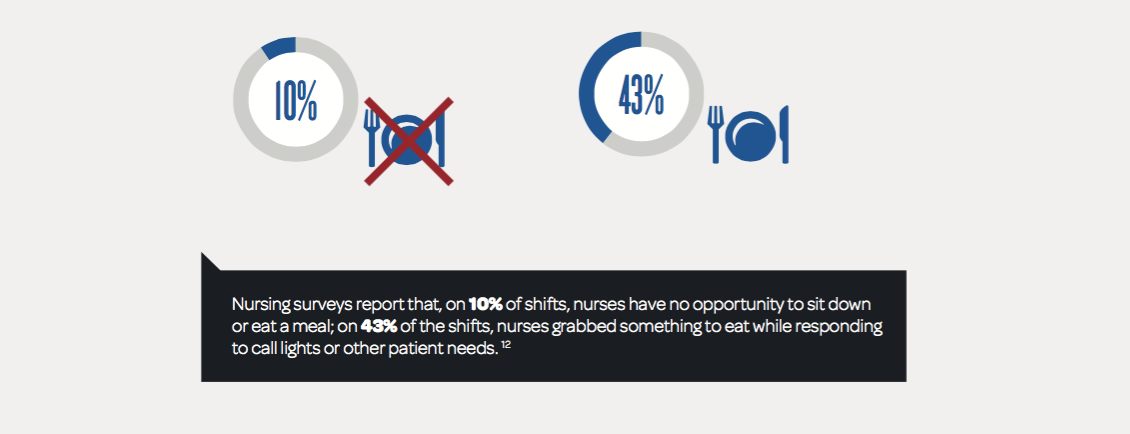

11. Nursing surveys report that, on 10% of shifts, nurses have no opportunity to sit down or eat a meal; on 43% of the shifts, nurses grabbed something to eat while responding to call lights or other patient needs.

12. Nursing overtime lawsuits are on the rise, and the inability to break for meals is a common issue.

13. The Medical Group Management Association found that the average utilization of operating rooms at large surgery centers was only 53% in 2013.

Take Two Server Arrays and Call Us in the Morning

The good news is that it is possible to create schedules that change this dynamic. It requires a lot of computing power and the assistance of data scientists who can create models that reflect an organization's real-world constraints. With the proper tools to model the possibilities—even the huge numbers of possibilities associated with optimizing the sequence of appointment slots—data science can replace the fly-by-the-seat-of-your-scrubs approach that ails us. Given the pressure already present in the healthcare system—to improve patient and practitioner satisfaction; to reduce wait times, costs and waste; and to deliver services to more people more efficiently and effectively—the adoption of data science-designed schedules is a relatively easy pill to swallow.

Mohan Giridharadas is founder and CEO at LeanTaaS. Before starting LeanTaaS, Mohan led the Manufacturing and Service Operations practice at McKinsey & Co. in the U.S. and the Asia-Pacific region. He is on the faculty of the Continuing Studies program at Stanford University and the MBA program at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley. He holds an MBA from Stanford University, an MS in Computer Science from Georgia Tech and a B Tech. in Electrical Engineering from IIT Bombay. For more information on LeanTaaS, click here.