Historically, for-profit health systems avoided graduate medical education (GME) programs based on the perception that teaching hospitals were costly and inefficient and the required academic credentials were unachievable for community-based hospitals, which comprise a significant portion of for-profit systems.

Unlike most of their academic counterparts, many for-profit hospitals and systems have not imposed caps on the number of resident FTEs that may be reimbursed for training.

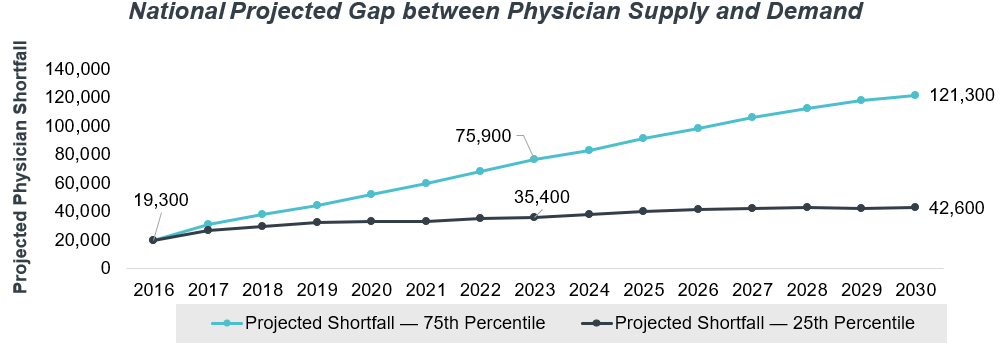

In the wake of changing market pressures and healthcare delivery needs, for-profit systems have begun to embrace GME as a vehicle to solve the projected primary care physician shortage (illustrated in figure 1) while supporting the underserved in many of their geographies. Developing primary care teaching programs in select community hospitals is a strategy that many for-profit health systems are prioritizing to address some of their most significant organizational challenges.

Figure 1:1 National Projected Gap between Physician Supply and Demand

One of this article’s contributing authors, Don David, MD, is the chief medical officer (CMO) for a Southern California–based five-hospital extension of a national for-profit organization and had primary responsibility for its development of GME. He has provided commentary throughout this article on how GME was developed in the region, best practices, and lessons learned. These comments are boxed off for clarity.

I. Background

When the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) was established in 1981, it faced two primary stressors: variability in the quality of resident education and the emerging formalization of subspecialty education.2 While the teaching principles the ACGME reinforced were valuable at the time, they do not meet the needs of the contemporary healthcare delivery system. Therefore, the ACGME has modernized and teaching require-ments have evolved through the Next Accreditation System—and for-profit health systems have begun positioning themselves to solve today’s macro GME stressors: the need for pri-mary care, the importance of the learning environment to reflect patient needs, and the over-ly complex infrastructure requirements for residencies.

Large academic medical centers, university-based health systems, and safety net hospitals are commonly thought to be the most appropriate environments for resident training. How-ever, while this is generally true for highly specialized fellowships, it is often not the case for primary care training programs. The patient load and the clinical spectrum of patients seen in community hospitals offer an effective training environment for primary care residents. Addi-tionally, continuity clinic requirements for primary care can be met through community-based training programs using affiliated physician groups and federally qualified health cen-ters (FQHCs).

As internal medicine programs in major academic health systems often serve as feeders for more specialized programs, a significant portion of the residents in those programs have no intention of becoming primary care physicians and ultimately pursue subspecialty fellow-ships. In urban areas with multiple academic health centers, it can be a challenge to find the clinical volumes to provide residents with the continuity of care clinical experience required by the ACGME.3 The resulting competition often leads to citations for missing primary care volume requirements (thus inadequately training the residents) and unsatisfactory resident experiences. The academic infrastructure, which is required to support specialty-based aca-demics, includes a commitment to research, adding significantly to the cost of training. Pri-mary care resident training does not require such commitments.

Can you describe your organization and how did it decided to embrace GME on a large scale?

The organization owns and operates for-profit acute care and behavioral health hospitals across the United States. Our five-hospital system made the decision to explore how GME could support its regional strategy. The hospitals serve diverse patient populations within the market and offer unique areas of specialization. Although community physicians endorsed the general concept of training residents, many felt that the hospitals would not have the infrastructure to sponsor training programs.

The system viewed GME as a bridge to connect strategic partnerships. Even though the relationships did not materialize as initially predicted, the organization determined that GME was worth pursuing in its own right, and strategic relationships with new partners were forged.

II. Why Pursue GME?

GME can provide several benefits to large for-profit, geographically dispersed health sys-tems. For example:

» Culture: GME can create a culture of learning and an environment of inquiry. Hospital systems can use their training programs to align the system’s core values, and residents often establish practices in communities where they received their training and have nat-ural ties to the training hospital. This retention pattern can promote organizational culture, as the retained graduates embed learning principles into the clinical environment.4

How does the inclusion of GME elevate the culture of learning at the organization?

The addition of GME requires the medical staff (particularly in a community-based program that relies on its medical staff for faculty) to practice evidence-based medicine. Residents bring with them the newest practices and approaches to patient care, and the program directors must monitor and evaluate the performance of these practices. The presence of residents also requires nursing and pharmacy to keep abreast of changes in best practice. Overall, this translates into better care that should result in improved patient outcomes at lower costs.

» Productivity: With the appropriate supervision ratios and predictive scheduling, GME can enhance productivity in the delivery of clinical care. A precepting primary care physician can supervise up to four residents at any given time. Under that training model, physi-cians can experience productivity improvements in the ambulatory setting.5

» Quality: Residency programs inherently have quality of care integrated; this is a key area of emphasis in GME training. Studies have shown that GME will drive adoption of evi-dence-based practices and use of standardized order sets based on best practices that have resulted in a reduction in hospital readmission rates and improvements in other val-ue-based purchasing quality metrics.6

» Recruiting: As previously mentioned, residents are likely to practice where they trained. In 2016, 47.5% of physicians were active in the state where they completed their most recent GME, and retention rates were highest among physicians who completed both UME and GME in the same state.

» Primary Care: Unlike many academic entities, community hospitals are ideal hosts for primary care training, providing care and educational experiences with diverse panels of patients. The availability of a resident continuity clinic for unassigned patients may also reduce readmission to the hospital.

» Economics: GME may provide vital reimbursement to support the teaching mission. It is essential, however, that the program be structured appropriately to ensure it receives the maximum federal and state funding available.

You joined your organization after its decision to embrace teaching on a broad scale. What attracted you to the opportunity?

As the CMO for the regional system, my role as physician, clinician, and organizational leader quickly led me to conclude that GME could not only address the points above but also serve as a connective force to enable the medical staffs of our respective facilities to accomplish common goals. The quality component associated with the residency program also supported our organizational mission and, we felt, could anchor those initiatives at our hospitals where residents were present. I felt it was important to spearhead the GME initiative in addition to my CMO duties so the community physicians could see the resources the organization was putting behind this opportunity.

III. Critical Issues

Pursuing GME is a complex organizational strategy rife with potential pitfalls that could affect the organization’s success. Residents, while a tremendous source of service delivery capaci-ty, will fundamentally change the organization and its approach to clinical care. Achieving the benefits previously discussed requires dedication to managing multiple challenges. These include:

» Reimbursement: To ensure the hospitals receive appropriate reimbursement from CMS, a series of administrative and operational changes must be orchestrated. It is essential to consider the impact of the per resident amount, program cap amount, and cost-based re-imbursement and to avoid triggering the program cap development clock until the organi-zation is prepared.

» Timing: A well-choreographed implementation plan is needed to ensure that the transition of community-based program faculty allows clinicians to maintain private practice or hospital medicine service as the program ramps up. New program development should occur within a five-year window, with special attention paid to optimizing the resident cap.

» Economics: The potential training site must conduct its due diligence to confirm that its reimbursement profile makes program support viable. Cost variables and drivers, as well as start-up costs, will vary by program and must be modeled in detail.

» Program Mix: It is important to select programs with high strategic value that the facility can support. The potential mix will be based not only on strategic need but also on indi-vidual program economics, availability of subspecialty training faculty/other partners, identification of program directors and core faculty, and an assessment of local competi-tion for high-quality faculty and trainees.

» Partnerships: Community partners can enhance the educational experience and mitigate training costs. GME also serves as a point of common ground to create strategic partner-ships with faculty providers. Partners to consider include FQHCs, medical schools, local physician groups, and contracted physician service providers.

How did your organization decide which medical school to partner with?

After exploring possible partnerships with large, basic research–focused medical schools, our leadership team took a step back to reevaluate the need for and role of such relation-ships. While these partnerships could provide an easy solution to the problem of demonstrat-ing scholarly work and to the administrative infrastructure needed to support GME in a GME-naïve organization, these partnerships typically require ceding some level of control to the academic partner. Our organization decided to pursue a close, but nonexclusive, relationship with a nonresearch-based medical school that had an established track record of graduating physicians who entered primary care and tended to remain in the local market after graduation.

» Faculty Recruitment: Identifying program directors and requisite faculty is critical—to starting a new program as well as meeting downstream timelines. Moreover, modern re-cruitment strategies are designed to recruit not only key faculty but also medical stu-dents, residents, and fellows.

How did you address the challenge of program director and faculty recruitment?

Early in the process, a selected designated institutional officer established an institutional Graduate Medical Education Committee, including key community physician stakeholders (who could be potential core faculty or program directors), to approve an institutional application. After a focused search, we identified program directors for internal medicine and family medicine. Given that the state in which we operate does not allow the direct employment of physicians, the program directors were vetted and employed as faculty by the medical school partner. The program directors then helped to recruit select core faculty, specialty faculty, and program coordinators. We were fortunate to find numerous candidates in our market who had the requisite academic credentials to serve as director and associate program directors. Local physician practices serve as our subspecialty educators.

IV. Key Strategic Variables

Each facility, community, and/or marketplace will face a unique set of circumstances that will affect its ability to host and train learners effectively. Likewise, individual markets will need to assess the value of GME based on their respective strategies. Variables to be con-sidered include:

» Market Needs: It may be appropriate to move forward with an investment in teaching even if it will not contribute positively to the facility’s bottom line. Communities with un-derserved populations or physician shortages should consider this investment to support their strategic vision.

» Service Line Expansion: Where certain specialty services can be supported, select fel-lowships can be established to achieve strategic initiatives. These fellowships often re-quire partnerships with medical schools and other practitioners to provide or enhance the requisite training.

» Strategic Partnerships: Affiliations may be required to achieve initial program accredita-tion and subsequently represent avenues to enhance care delivery. Forming partnerships (for example, with a medical school, private physician groups, and/or FQHCs) to support the teaching experience can forge stronger community relationships and result in greater collaboration in the provision of care.

» Physician Support: Training often necessitates support and buy-in from community phy-sicians. The interaction between community physicians and residents, coupled with a new economic arrangement between the physicians and the hospital, can enhance clini-cal throughput for both groups.

» Physical Space: Each new program will require dedicated space, with the type and amount dictated by the type of program and number of residents. Resident call rooms of-ten represent a challenge to many hospitals, as they must be proximate to patient care rooms.

» Capital Investments: Meeting space requirements may require capital investment for re-modeling or even acquisitions. The timing of such investments must be considered when deciding on the timing of the program start-up. It is important to appropriately classify these costs, as some capital expenses can be recovered as allowable program start-up expenses.

V. Basic Tenets of New Program Development

Once the decision to become a teaching organization has been made, several tenets apply to the development of the program(s) and affect choices about size and complement. These include:

» Growth: Go big! A new teaching organization will have only one opportunity to establish a resident cap—therefore, growing the program as significantly as warranted, within the five-year cap development period, will provide options for future growth. This strategy may allow for future fellowships, affiliations with other teaching programs, or the devel-opment of alternative programs.

» Sustainability: The GME enterprise should be developed in a manner that is consistent with the organization’s strategy and mission, as well as community need. Economic sus-tainability that balances operational and academic demands is critical. The teaching model must be embraced by the organization and embedded in the clinicians’ culture.

» Partnerships: GME partnerships can be crucial to residency programs’ success. Select-ing the right partners based on need, strategic fit, and desired long-term collaboration can provide benefits beyond those traditionally tied to GME. Among these are strong ties with physician groups, stronger relationships with community agencies and medical school partners, and enhanced delivery capacity for the community’s underserved population.

How did you approach community partnerships, and what was their perceived value?

As previously mentioned, our organization originally envisioned GME as a bridge to strategic partnerships. Some of those partnerships are still being negotiated, but what we found to work best in the various communities we serve was to find partners—academic organiza-tions, multispecialty groups, and community physicians, to name a few—who embrace the same values in GME that we hold important. We sought partners who could provide a primary care–focused, training-driven, and nonexclusive relationship to give our future learners the greatest flexibility in gaining the skills needed to serve our community.

Each facility or organization will rise to meet the challenges facing it; our approach was one of collaboration and mutual benefit to assemble the component pieces of education that will provide the most value for all the stakeholders.

» Personnel: To the extent possible, key GME positions should be filled by physicians al-ready in the organization’s system. Program directors and core faculty will be the face of GME in the organization and need to fit the organizational culture and promote an envi-ronment conducive to education and training. Various employment models can be used to ensure program leadership stability and mitigate “markup” of faculty stipends.

Are you considering additional fellowships or other residency programs—beyond primary care?

Although primary care is our focus, we are considering other select residencies and fellowships. We have planned for residencies in emergency medicine, neurology, obstetrics and gynecology, and psychiatry, as well as potential fellowships in cardiology and critical care.

VI. Finding Solutions for the Primary Care Physician Shortage

As the demand for primary care physicians continues to grow, alternative models and ap-proaches need to be explored. Given that for-profits have a significant presence in nonurban geographies where large academic organizations historically do not deliver care, there is an opportunity for novel, expanded primary care models. These hospitals are ideally suited for primary care training, given their patient mix and relationships with local physician groups. Additionally, new teaching hospitals in these communities can support care for the under-served while training residents in the locations where they are likely to practice. Residents who train in community-based settings are introduced to and embrace the training and su-pervision models of the teaching service that generate significant throughput metrics of tradi-tional private practice models.

Establishing teaching in historically nonteaching community hospitals has inherent challeng-es. Among those are finding qualified program directors and assistant program directors. An increase in the number of hospitals starting teaching programs, coupled with the ACGME’s requirement for previous academic experience (five years’ total GME experience, with three years’ administrative GME experience in the case of internal medicine), has reduced the pool of eligible candidates. Rural locations can present additional recruiting challenges. It is also important for affiliated medical practices—which will be integral in key training roles such as providing the subspecialty experiences residents need to graduate—to be supportive of the new teaching mission. However, as the case study demonstrates, a well-planned and well-executed introduction of teaching to historically training-free environments can effec-tively align the academic mission to efficiently managed community hospitals.

What’s next in GME for your organization?

GME has proved to be a very effective way to solidify relationships with medical groups, and it appears to be helping pave the way to partner in gainsharing opportunities and joint efforts to improve population health.

1 Tim Dall et al., “2018 Update—The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2016 to 2030” (IHS Markit, March 2018).

2 Thomas Nasca, Ingrid Philibert, Timothy Brigham, and Timothy Flynn, “The Next GME Accreditation System—Rationale and Benefits” (New England Journal of Medicine, March 15, 2012).

3 Jeremey Walker, Brittany Payne, B. Lee Clemans-Taylor, and Erin Snyder, “Continuity of Care in Resident Outpatient Clinics: A Scoping Review of the Literature” (Journal of Graduate Medical Education, Vol. 10, No. 1, February 2018, 16–25).

4 Andy Anderson, Deborah Simpson, Carla Kelly, John Brill, and Jeffrey Stearns, “The 2020 Physician Job Description: How Our GME Graduates Will Meet Expectations” (Journal of Graduate Medical Educa-tion, Vol. 9, No. 4, 2017, 418–420), https://www.jgme.org/doi/10.4300/JGME-D-16-00624.1.

5 Jeremy Ellis and Richard Alweis, “A Review of Learner Impact on Faculty Productivity” (American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 128, No. 1, 2015, 96–101), https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(14)00851-1/fulltext.

6 Paul Batalden, David Leach, Susan Swing, Hubert Dreyfus, and Stuart Dreyfus, “General Competencies and Accreditation in Graduate Medical Education” (Health Affairs, Vol. 21, No. 5, 2002, 103–111).