Strategy is easy to define when there is one clear and actionable objective, however, a narrowly defined strategy does not work for wide-ranging problems such as improving the mental healthcare system in the United States.

Mental health parity requires a multi-faceted approach to address the layers of issues and disparate interests that have accumulated over the years. Determining where to start and the best approach can be a daunting task.

In the case of fixing the mental healthcare system in the U.S., it may be less important to know precisely where to begin, but rather, to understand that we need to get started. Within the complex network of policies, organizations, and providers, no single entity is going to pick up the tab, nor is one organization going to have all the answers or the "correct" perspective as each scenario and organization will require a uniquely tailored solution. In addition to end-of-life care, mental health is one of the largest areas of healthcare spending, but it is also one of the least addressed areas in healthcare reform. Public and private sectors must find ways to collaborate and communicate efficiently to improve the state of mental healthcare in the U.S.

Quantifying the problem

More than 60 million Americans, or one in four, live with some form of mental illness in the United States. Of those, 14 million live with serious mental illnesses (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder, etc.) and die an average of 25 years earlier than the general population. Additionally, approximately 41,000 Americans commit suicide each year, most while suffering from acute mental illness. It is estimated that when Medicare, Medicaid, disability support and lost productivity are tallied, the total cost of non-treatment to the government is as much as $317 billion per year.*

*It should be noted that what often gets missed are the costs associated with incarcerating people in the U.S. jail and prison systems. About 356,000 U.S. inmates have a diagnosed mental illness. Assuming the cost of housing each of these inmates is $50,000 per year, this equates to an additional $17.8 billion in spending.

The underlying principle that should guide fixes to the mental healthcare system is all individuals have a fundamental right to pursue a life that includes a healthy mind and body. That includes ensuring that "hygiene factors" – those things on which politicians create their campaigns – are being met, including living wages and affordable healthy food, housing, daycare, and education. As one psychologist John Keyes asked, "How can we work with depression in the context of people having to work at low wage jobs, eat cheap processed food and live in cramped dangerous urban environments?" The hygiene factors are things that must be tackled at a societal level, but as healthcare organizations and professionals, we can act on four specific areas to improve mental healthcare in the U.S. which will guide us to better outcomes:

1. Improve access to care

2. Improve care delivery and coordination

3. Remove the stigma of mental illness

4. Educate the employer, the patient, and the caregiver on their responsibilities

Improve access to care

Yes, it is still a problem. While access to care has been improved to some degree with the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Americans with mental illness have one of the lowest rates of health insurance coverage. Making sure they have insurance coverage is important to addressing this societal issue. There is a reported shortage of mental health professionals, with only one per every 790 citizens in the U.S., leading to access issues in many parts of the country. Broadly defined, "mental health professionals" can include social workers, therapists, psychologists, or psychiatrists. A mere 55% of psychiatrists accept private insurance (compared to 89% of other doctors), and only 43% accept Medicaid patients (compared to 73% of other doctors). Primary reasons for defaulting to an out-of-pocket payment are frustrations regarding burdensome reviews by insurance companies and lack of administrative support needed to handle the administrative workload of claims processing with insurance companies and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

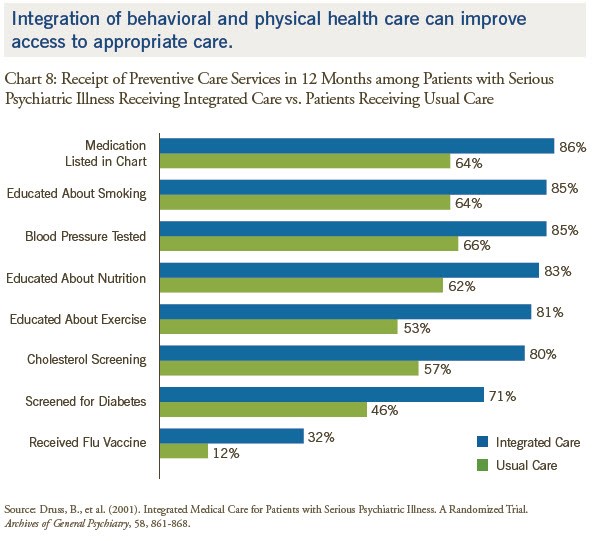

Patients with mental illness often do not get adequate primary care, which can further exacerbate their mental illness. There appears to be a need to integrate primary care into mental health care, and vice versa.

Those who go untreated will have continued impairing symptoms, which can affect their productivity and quality of life for years. Reducing the symptoms of those on the verge of hospitalization should be a key goal. According to Dr. E. Fuller Torrey, president of the national nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center, "Assisted outpatient treatment has proven to reduce psychiatric hospitalizations by more than 70 percent."

In order to improve access to care for those suffering from mental illness, the processes surrounding insurance and government reimbursements should be simplified in order to enable mental healthcare professionals to focus more of their time on patients. Further, providers should integrate mental health as part of the care delivery model in larger healthcare systems in order to widen access to care.

Improve care delivery and coordination

The mid-20th century saw the fall of many mental health institutions that stemmed from a movement among the psychological community to shift to a community based model, despite a lack of clinical evidence the shift to a community model would work. However, mounting pressure from the public after investigative journalism uncovered inhumane treatment of the institutionalized mentally ill accelerated the shift.1a The shift in the 1960s from centralized federal programs to more community based programs run by the state and local governments saw that in reality, the community models did not treat or accept the severely mentally ill.1b The community model funding eroded by the end of the 1980s. Since then, the criminal justice system has become the default front line of care for many of the severely mentally ill in the United States. (For example, Cook County Jail in Chicago is the largest inpatient mental health facility in the country). Modern treatment of mental illness is now composed of a highly fragmented environment, including a wide range of care locations and payers. Aside from those in the criminal justice system, patients may go to psychiatric hospitals, hospital wards, medium and long-term care facilities, and halfway houses, or in less severe cases, outpatient clinics.

If larger health networks and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) continue to be the trend, there may be an improved ability for patients to navigate the system in a more coordinated way. Payers can provide mental health as a core part of their practice offering rather than considering it a separate business that is to be handled only by an ancillary mental health partner. Providers can look to consolidate practices, so they can accept broader patient pools and gain the back office support they need to work with payers. In this way, better integration and coordination of care can be achieved across the payer-provider bridge. For example, a key step that should be made is to integrate mental health records into all electronic health records (EHRs) as they have historically been kept separate. This type of integration would allow providers to see other health factors that influence mental health.

"If I'm treating somebody for depression, and they are not managing their diabetes, we know that these things interplay." – Dr. David Oslin, Chief of Behavioral Health at Philadelphia VA13

While technology should not be viewed as a silver bullet, it should be considered as another tool in the overall problem solving kit. Aside from integrating mental health into EHRs, social networking to combat depression is proving to be valuable, and companies like Ginger.io are leveraging apps to share mental health data with providers to improve care and coordination. However, further outcomes-based studies are needed to validate these approaches.

Remove the stigma of mental illness

Even with continued nationwide efforts to educate the population on mental illness, there remain widespread barriers in the form of stigma that have prevented progress in mental healthcare. Mental illness is among our deepest fears, and talking about mental illness is still taboo in the U.S. This is a societal problem that is pervasive, affecting all individuals including those with mental illness. Common and deeply held beliefs lead to discrimination against those with mental illness. The most commonly held belief is that the mentally ill are dangerous, hard to talk to, or that their specific mental illnesses (e.g., binge eating disorder) are self-inflicted.

Other stigma comes from the legacy of the institutional abuse that led to the fall of large healthcare institutions.1c Some may be attributed to a false belief that if one just "toughs it out" things will magically get better. Regardless of the source, the stigma is self-perpetuated – the fear causes people to label the mentally ill as "other", and mental illness is hidden rather than treated out of fear of being discriminated against by employers, peers, friends and family. Physicians may even be the most reluctant to ask for help if they have a mental illness and may factor into burnout or even suicide.

One example of the ways that payers can combat this stigma is by partnering with organizations like BringChange2Mind.org (BC2M). By working with organizations like BC2M, payers can raise awareness of mental illness and co-develop targeted interventions. BC2M's mission is "to end the stigma and discrimination surrounding mental illness through widely distributed Public Education Materials ... to act as a portal to a broad coalition of organizations ... [in the] treatment of mental illness." As the BC2M mission states, a broad coalition of patients, providers, and healthcare organizations is needed in order for the messaging and outreach on mental health to gain the attention it deserves.

Educate the employer, the patient, and the caregiver on their responsibilities

What is the difference between a psychologist and a psychiatrist? Most people probably couldn't tell you that the psychiatrist is a physician who has gone through medical school and a residency training in mental health and who also has prescribing privileges. Psychiatrists often can charge more than a psychologist. Psychologists go through five to seven years of graduate work to attain a PhD (Doctorate of Philosophy) or PsyD (Doctorate of Psychology). Most psychologists do not prescribe medication, aside from two states (Louisiana and New Mexico) that allow it when a psychiatrist has been consulted. Many other avenues of care exist beyond this including social workers, therapists, and masters level clinicians. Knowing the difference between them has large implications to the cost and type of care one receives.

Better patient education and engagement is needed not only to reduce the stigma of mental illness that pervades American culture, but also to know what the signs of different mental illnesses are and where to go for help. For example, patients should be aware that psychiatric medicines can be very effective, but that they can also potentially mask problems and become addictive. The patient must take responsibility for his or her own care for it to work – the key concept of patient engagement – and be willing to seek assistance when it is needed.

Employers should recognize they have responsibilities beyond checking they have the box that they have an Employee Assistance Program (EAP). EAPs are good, but only help after a crisis has erupted. Aside from health coverage, building a healthy work culture is the best preventative medicine to stem mental health issues and to help employees thrive. Workers who have a mental illness or a family member with a mental illness may be physically and emotionally drained at times, so a supportive work culture is critical to preventing burnout and eliminating any perceived or actual discrimination when they need to get to (or a loved one to) an appointment mid-week.

Caregivers come in many forms – family members, friends, inpatient/outpatient staff – and they should all have information on hand as to how a specific mental illness can manifest itself so they know how to respond to crisis situations (e.g., manic episodes, suicidal ideation or attempts, etc.). Additionally, knowing what a patient's support network is as a caregiver ensures the caregiver does not burn out and can share care responsibilities. It can take a toll physically and emotionally if the caregiver feels he or she is alone in providing support.

So what next?

By looking to improve access, care and coordination, reducing the stigma of mental illness, and educating patients and employers, one may not solve all of the problems of the mental healthcare system, but they can make a meaningful and noticeable difference. Heading down this path will not be easy, but the opportunity to save many lives and billions of dollars is worth the journey. You've just got to start; Contact Vynamic to see how we can help.

Resources:

- Bell, Carl C. "From Asylum to Community: Mental Health Policy in Modern America." JAMA. 1991; 266(22):3205-3205.

Matt O'Dell is an experienced management consultant with over eight years in the healthcare and high-tech sectors. He is passionate about strategy and innovation in healthcare and holds a B.S. in Marketing and Operations Management from Indiana University - Bloomington, and an MBA from the University of Notre Dame.

Dylan Casey is a healthcare industry management consultant focusing on the public health and life sciences sectors. He comes from a background in engineering, having graduated from Villanova University with a B.S. in Chemical Engineering.

Mindy McGrath has over 20 years of experience as a healthcare industry leader and management consultant. In her current role as Vynamic's Healthcare Industry Learning Lead, she delivers insights and training to the Vynamic team and clients about current topics in the healthcare industry. Mindy holds a B.A from LaSalle University and an MBA and MA in Health Economics from Vanderbilt University.

Kevin Flintosh has spent more than eight years in the healthcare consulting industry. With a degree in Journalism from Penn State, his work often focuses on communications, training, and change management to ensure efforts are valuable to their audience.

The views, opinions and positions expressed within these guest posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of Becker's Hospital Review/Becker's Healthcare. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.