An unusual value analysis team leads effort to reduce costs and variability of utilization across a system of care

In the fall of 2011, a cross-functional team at Our Lady of Lourdes Regional Medical Center in Lafayette, La., began work to achieve a long-sought goal: reducing the overuse and improper use of antibiotics.

The project utilized a new software application that aggregates data from disparate systems, such as physician order entry, purchasing and finance. The data are arrayed on dashboards that reveal physicians' ordering patterns, the drugs being used throughout the hospital and the costs of those drugs.

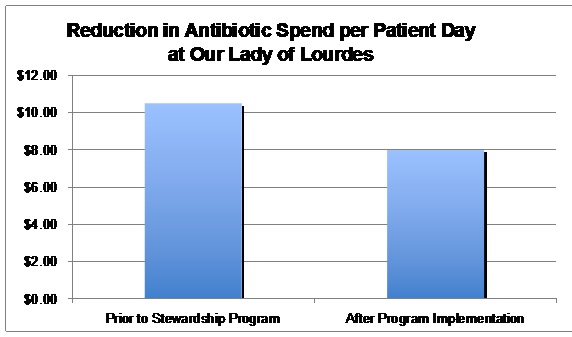

The goal wasn't for supply chain or finance to tell physicians what to do. In fact, the effort was led by physicians, who were supported by a supply chain team that includes nurses and other clinicians. The result was a new antibiotic stewardship program that conserves front-line antibiotics, the improper use of which has contributed to the rise of multi-drug resistant organisms and reduced efficacy of current drugs. Now, when three different antibiotics are ordered for a patient, or if an antibiotic from a targeted list is ordered, an infectious disease physician is called in for a consult. The hospital saved 25 percent on its antibiotic spending from fiscal years 2012 to 2013.

The project is a microcosm of Healthy 2016, an improvement initiative of Our Lady of Lourdes' parent, Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System. Launched in 2011, Healthy 2016 is a multifaceted effort, with interwoven strategies related to care for seniors, performance improvement, healthcare redesign and financial viability. These collective and coordinated efforts together are intended to prepare the organization to thrive when forces beyond its control truly begin to affect healthcare across the country.

Like most healthcare providers, FMOLHS is working to achieve efficiencies in an era when Medicare is reducing payments and consumers are paying more out of pocket for their care. The plan has an ambitious target of $165 million in savings over five years, of which $19 million would come from supply chain and an equal amount from reducing clinical variation.

In many organizations, supply chain is eyed solely as a means of reducing costs, using traditional techniques of pricing and sourcing. At FMOLHS, a more holistic approach is utilized, taking advantage of a more clinical focus and building new relationships with physicians, who drive much of system spending.

Breaking through silos

FMOLHS has already achieved $20 million in supply chain and clinical variation savings. More importantly, it has earned a key role in helping to achieve a greater sense of "systemness" within FMOLHS, says President and CEO John J. Finan Jr.

Even though FMOLHS has hospitals that have been around for more than 100 years, it has not had a long history of functioning together as a system. Its five hospitals are widespread in Louisiana. One hospital joined in 2004; another was acquired in 2014. The supply chain function is one of the areas coordinated at the system level, though even it is decentralized by having most of its staff working at the individual hospital level.

Healthy 2016 is aimed in part at the idea of "systemness." A system steering committee was created and tasked with coming up with a list of opportunities for efficiencies (see box). It came up with more than 60, and senior leaders picked 52 in the categories of labor, productivity, clinical variation, supply chain and others. For each area, an accountable leader was identified, along with an executive champion. Quarterly meetings are held to discuss progress, and the results are disseminated broadly.

A study of mesh

Dr. Richard Vath, CMO of FMOLHS' flagship hospital, Our Lady of the Lake Regional Medical Center in Baton Rouge, was put in charge of the effort to reduce clinical variation. He began his work by looking for a likely candidate for a pilot project. He found one that might not lead to too much acrimony: surgical mesh. At the time, Dr. Vath's hospital utilized 18 kinds of mesh in different categories.

His team brought in a leading technology assessment company, which analyzes the comparative effectiveness of medical products, to examine the literature. Dr. Vath wanted to try an approach usually applied by pharmacy and therapeutics committees. "We wanted to make it like presenting a clinical case study, looking at efficacy and costs, as well as all clinical indications," he said. "Could we reduce the number of products, vendors and contracts without sacrificing quality?"

All surgeons who use surgical mesh were asked to attend a meeting where the data were presented. "They reviewed all the data, and at the end determined that the data was limited. We were able to look at the safety profiles from the FDA recalls and anything else we could find on quality. We found that if we narrow these 18 kinds of mesh down to six, there was no evidence that quality would suffer and we would save roughly $500,000 annually," Dr. Vath said.

Though there was a general agreement, he said those kinds of discussions often lead to little change, so he asked the surgeons to actually vote on the decision and verbally commit to follow through. "You could tell this was new territory for them, to be consulted in this way and asked to take a stand," Dr. Vath said.

A 'spine cap' program

After that early success, subsequent efforts were applied to total joint and spine implants and in cardiology, where a recent discussion about the use of peripheral vascular products spurred thoughtful discussion about possible product consolidation efforts.

The spine project was a result of a physician request that Our Lady of the Lake allow in a new, higher-cost spinal implant vendor. The hospital already had more than 15 spine vendors, and the request opened up an opportunity for investigation.

Dr. Vath identified a lead spine physician for this project, who worked with value analysis to put together usage patterns and costs for implants by vendor and by individual physician.

To convey the sense of physician ownership of the process, the lead physician took the data to a meeting of all of the spine surgeons. The initial proposal to the surgeons was to reduce the number of vendors to achieve the best prices possible, without any loss in quality. After long and productive discussions, the surgeons voted instead to adopt a "spine cap" program that attempted through the use of a dollar limit per procedure to reduce the variation in cost of products utilized. The cap is based on industry benchmarks.

A second meeting was then held with all of the vendor reps, the CMO, the chief nursing officer, other senior leaders and the supply chain team. Vendors were informed of the plan and told they could continue to compete if they met the cap by an agreed deadline.

The importance of having surgeon buy-in was seen when a couple of vendors balked at the spine cap. The physicians reached out to the vendors, telling them they would cease using their products if they failed to comply. The vendors all met the needed pricing.

The spine cap project is projected to achieve $2 million in savings annually.

The total joint project, which involved reducing the total number of vendors, has achieved another $2 million in savings.

Further savings are realized when, during the course of the contract, FMOLHS is able to determine if it is on track with commitment levels from suppliers under terms of their deals, such as buying 80 percent of an agreed total spend to get a particular price.

Software assist

In the cardiology area, the same software application used on antibiotics — Optimé Supply Chain's SmartANALYTICS — played a key role. One of the key issues faced by FMOLHS is access to enough valid data. Using the application's dashboards on utilization and price, broken down by vendor, hospital, category and physician, staff could paint a picture for the physicians on the quantity of different products to facilitate peer discussions around utilization.

The system is looking to fully integrate its cost and supply chain system, allowing FMOLHS to interface with the clinical system. The utlimate goal of this is to easily download data on the actual procedures performed by clinicians and all of the costs associated with that procedure.

FMOLHS is looking to the Food and Drug Administration's new Unique Device Identification program, which begins a seven-year rollout in fall 2014, when all implantable medical devices will be able to be barcoded and scanned at the point of entry and use. Today, just getting a handle on what is available and what is used in the OR is a painstakingly difficult manual process.

New product review

For new product requests, Dr. Vath took a novel course. One of the biggest obstacles to reducing supply costs is the proliferation of new products, often after one surgeon requests it and reports on anecdotal success with it. The process at FMOLHS used to be handled in a scattershot fashion through various medical committees and by the nursing and supply chain processes.

Dr. Vath formed a new Medical Executive OR Supply Committee in 2012 and placed a respected general surgeon, Dr. V. Keith Rhynes, in charge. This group included all the surgical specialties. Now, instead of just going to nurses or supply chain, a physician who wants a new device must present his case to the new committee, including all the data from the value analysis staff and outside groups.

"The docs on the committee ask all the tough questions about the data, about why this is necessary and about any conflicts of interest the physician might have," Dr. Vath said. "Then they excuse the physician requesting the device and have a dialogue about the request in the context of the bigger picture with the overall OR supply chain spend. There really must be data showing this product is superior in quality to get it approved."

"When cost and utilization information is put in front of our physicians, and it is valid data they can trust, their reaction has been transformational," Mr. Finan says. "Doctors are really equal partners with us. In this new era, understanding that payment is changing means we must all adapt our behaviors."

The only real limitation of this effort is how quickly data gets to physicians. "We are looking to streamline this process, to be able to get the supply-chain people the data they need faster so they can aggregate it much faster and then we can present much quicker," Dr. Vath said. "The state of comparative effectiveness research is still very early, and we need to work internally on this process."

A key role for value analysis

Dr. Vath credits the value analysis team of nurses and some other clinicians on the supply chain team as a bridge between administration and the clinicians in helping to garner executive-level support for change. "We have had to take successes at one hospital and apply them to other system hospitals, where it plays out a little differently at each place. The conditions are quite different at each hospital, but having someone well-versed in what work has been done at another facility has been essential."

FMOLHS has 10 clinical and non-clinical value analysis teams throughout the system, including surgery, cardiology, pharmacy, core nursing/women's health, radiology, lab/respiratory, ortho/neuro, dietary/nutrition, facilities and admin/ad hoc.

Supply chain provides a team of seven clinicians and three non-clinicians, who are called resource utilization managers. They support each of the value analysis teams, as well as new product and technology review and approvals using evidenced-based methodology.

With six nurses, a former cath lab manager, a former lab director, and a former dietary services manager, the team is uniquely qualified to identify supply chain integration opportunities.

Getting a handle on contracting

Of course, much focus in the supply chain has been on managing of contracts, pricing and consolidating of vendors. Part of the challenge has been simply making sense of contracting. There was no central repository for contracts; contracts were on lawyers' desks or desks in a hospital office. Some were on paper, some online. There was no capability to determine whether the organization was compliant with contracts, and no method for exploring the clinical efficacy and value of the different supplies the organization was using, particularly for physician preference items.

In 2011, FMOLHS began working with Optimé, which first brought in an application that manages sourcing, contract negotiation and vendor selection, and also has a contract repository. The application has become the health system's corporate database for all supply chain contracts. FMOLHS has integrated it with its e-procurement solutions, and the organization is continuing to populate the application with data as new initiatives that require project management arise.

The software has a product management workflow piece that allows service line staff to manage tasks around contract renewals. It also helps manage the flow of information with FMOLHS' supply chain partner. Knowing where the system is on contracting helps it get best practice pricing and GPO service agreement maximization.

Perhaps the biggest remaining hurdle is how best to translate projects at one hospital to the rest of the system. Each hospital has different market challenges, processes and relationships with physicians. The CMOs of the five hospitals work together closely, but recognize that change has to happen at the local level.

This work will be ongoing, as optimizing the cost and utilization of medical products is dependent on several factors, such as new devices entering the market and changing consumer demands. But a new way of approaching these issues has been established, one that brings together materials managers, nurses, analysts and physicians to make the best use of scarce resources.

Kathy Chauvin, RN, is health system director of resource utilization and value analysis for the Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System in Louisiana.

Ed Hisscock is the co-founder and CEO of Optimé Supply Chain, Inc., a Skokie, Ill.-based company that delivers software solutions for supply chain optimization.