Hospital executives face a predicament. How can they improve inpatient capacity today while planning for a future in which demand for inpatient services is expected to decline? Industry forecasts before COVID-19 already predicted lower demand for inpatient services. Following the pandemic, an even greater shift away from the conventional inpatient setting is likely, as providers seek to separate “well” and “sick” patients. Such cohorting will separate generally healthy patients (e.g., those seeking elective procedures or routine care) from those who are sick and seeking care for chronic or life-threatening illnesses/conditions.

Some care that would traditionally remain in the inpatient setting will shift out of large hospitals into specialty centers focused on maternity care, rehabilitation, behavioral health, or even hospice care. And yet that is little consolation for hospital executives whose inpatient bed units currently exceed capacity.

In preparing for the future, facility planners are helping hospitals reexamine their historical assumptions around inpatient unit capacity standards and establish new expectations that accommodate their mid- and long-term visions, both as single entities and as part of larger, more integrated health systems. Hospitals should utilize evolved capacity standards to position their existing units for today’s capacity while also being resilient to the changes needed to adapt to the care standards in the future.

Impact of Industry Trends on Capacity Planning

Over the past decade, the role of the conventional hospital has been roiled by changing volume trends, evolving patient expectations, and unconventional competitors entering the industry.

Between 2014 and 2018, the total utilization of inpatient services declined by 2% nationally, with conventional medical and surgical admissions dropping by 6% and 4%, respectively. Over this same period, the national utilization for obstetrics, mental health, and substance abuse each increased.[1] Combined, these trends mean that smaller, more specialized inpatient hospitals are needed with staff who are trained to care for a more complex mix of patients.

Alongside these volume trends, the cost for healthcare services has increased faster than inflation, with patients paying more for each service.[2] Healthcare spending is at the center of the national conversation, and companies such as Amazon and Walmart are primed to disrupt the industry by offering convenient, low-cost care. In this age of digital disruption to healthcare, consumers are navigating a set of new, differentiated services that threaten the conventional inpatient care delivery model.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further disrupted the traditional healthcare model.

- In an effort to increase access for patients, telehealth has been widely adopted by patients, clinicians, and health insurers as the delivery method of choice (and in many cases, after years of resistance).

- Furthermore, elective case cancellation has created a major shortfall in health system revenues.

- Finally, as COVID-19 cases surge, inpatient hospitals have adapted to accept an influx of patients who required updated care standards and strained hospital resources. While beds in some hospitals are full, other hospitals have seen unusual vacancies due to a surge that never materialized, illustrating an increasingly uncertain demand for inpatient care as a result of COVID-19.

As executives look to respond to these challenges, many hospitals are faced with aging infrastructure, outdated or inadequate clinical equipment, and capacity constraints that will require investment in net new inpatient units—without the volume and revenue growth to offset the depreciation and interest expense that will burden their income statements for years. With a 30-year useful life of most facility and capital investments, and the life cycle of change in technology and care delivery models in the single digits, the potential mismatch of investments to solutions is mounting. In this landscape, an updated approach to space planning is needed to ensure capital dollars are invested in new assets that are adaptable, resilient, and efficient.

Conventional Planning Standard Environment

Hospital bed planning is closely regulated by many states as part of a Certificate of Need (CON) process, and few updates to these standards or methodologies have been made since their inception.[3] These standards often dictate occupancy percentage targets for certain patient type units (e.g., 80% for med/surg), regardless of hospital size or considerations such as market share. In an environment where hospital systems are competing for new bed licenses through the CON process, many hospitals continue to plan around these standards, sometimes leading to option submittals that may not best meet their capacity needs—and create misaligned space allocations—in order to achieve regulatory approval.

While utilizing the state agency’s planning standards may be necessary for CON approval, hospitals must internally plan to more optimal standards by right-sizing units, investing in sites of care outside the inpatient setting, and working to define future hospital operations in order to minimize the capital investment needed.

Methodology for Updating Capacity Standards

Right-Size Market Forecasts

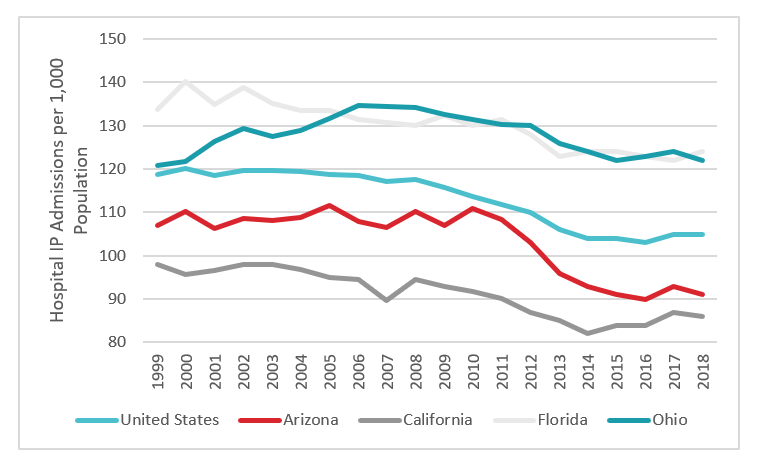

A first step in planning for a right-sized inpatient unit is to forecast the total size of the future market. Such calculations consider anticipated population growth and demographic changes (i.e., aging) as well as the anticipated utilization of inpatient services. Data at both the national and state level demonstrates that the inpatient utilization rate has begun to level off after nearly a decade of decline (see figure 1). With a growing population, this would indicate—at least on the surface—that the total need for inpatient services will increase in most markets.

Figure 1: Inpatient Utilization Rates in Selected States[4]

But when viewed in the context of accompanying trends that show declining conventional discharges (e.g., med/surg) and increasing utilization for substance abuse and mental health, a different picture emerges. The demand for hospital services is becoming more differentiated as patients seek more specialized care—and as they discover alternatives outside the inpatient setting. Payers and regulators are also shepherding this change, with a greater number of procedures being approved for the ambulatory setting (e.g., cardiac cath procedures, total joint surgeries) and alternative care models such as remote patient monitoring, medication management, and telehealth visits being approved for payment by more insurers.

In this context, how can hospitals gain a deeper understanding of their market and look beyond what is required to win CON approval?

- Refine market forecasts with seasonality and past census variation. Start by examining the seasonality of historical discharges and the corresponding patient classes that these variations affect. In most markets, winter census is higher on average than other times of the year because of flu season. In communities with large student populations, adolescent and young adult mental health census might spike in the spring or fall, in line with exam schedules and the college application process. In any case, forecasts and bed demand projections should be cross-referenced against past census variations to better understand the effect that planning to build and operate at the calculated capacity would have on the hospital.

- Determine the mix of services needed in the community. As a greater number of outpatient surgeries move out of the hospital setting into ambulatory surgery centers, and as urgent care centers or telehealth provide alternatives to the ED, conventional hospital services will be in less demand over time. Future hospital planning will require a better understanding of which competitors are in the market, what draws consumers, and what insurance companies are asking of healthcare providers.

Ultimately, the market for healthcare services will change, but hospital systems can help define the future of healthcare in their own communities. Hospital systems already provide much of the care within the community and may benefit from a strong brand reputation. Yes, Amazon and Walmart will disrupt the market; but health systems can be on the leading edge of this disruption by delivering high-quality care in the areas demanded by patients.

Consider Investment Outside the Inpatient Setting

A critical next step in capacity planning is identifying areas for investment outside the inpatient setting. Merely saying that patients will utilize telemedicine in the future or that home health will become a critical part of the care continuum will not solve the inpatient capacity constraints facing many providers today. Hospital systems must first attempt to forecast the demand for these services, in the context of the myriad factors driving change, and invest the capital and resources necessary to ensure these programs can thrive. Unlike before the pandemic, consumers are likely to be seeking a change in the care delivery model, and those health systems that offer a comprehensive solution that addresses community demands will establish a strong position in their markets.

Redefine Future Hospital Operations

Hospitals should set realistic goals to improve operations and reduce patients’ length of stay when planning inpatient units, such as improving day-of-discharge planning. At the same time, variations in census should be examined closely to identify any operational constraints that are inadvertently causing census spikes—and the need for additional planned beds.

- Optimize Hospital Throughputs. Prior to planning a definitive capital outlay for new resources, hospitals should review existing operating parameters for improvement opportunities. Reevaluating the hours of operation, room turnover times, and other efficiency metrics can help assets reach their most efficient use and increase capacity, without capital investment. When examining these measures, other suggestions come to mind: some literature suggests that operating room backups are the cause of high ED wait times, and other hospitals have experienced peaks in surgical inpatient unit census because surgeries only take place one or two days per week for high-volume specialties. Similarly, constrained resources in diagnostic and treatment areas can delay important procedures and prolong patient stays within the hospital

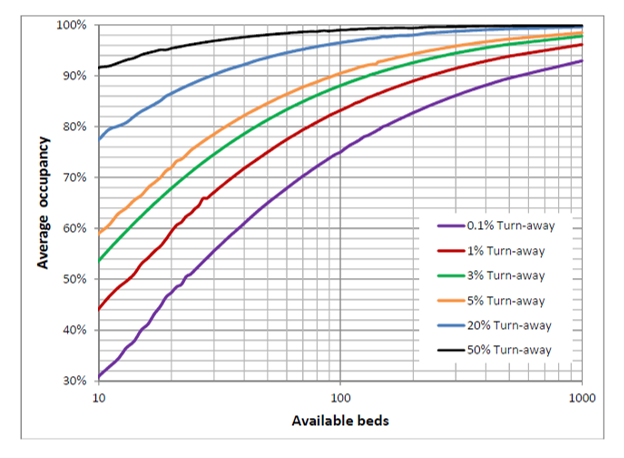

- Establish a Realistic Patient Turn-Away Rate. Many hospitals enter the capacity planning process with a target of zero patient turn-away days. While this goal is laudable on the surface, such an approach might cause a hospital to build far beyond its average daily capacity and spend more than necessary in capital and operating costs. The resulting sluggish operations could ultimately cause a hospital to shut its doors. Instead, a hospital should first look at improving its operations and eliminating bottlenecks to smooth census and drive down length of stay. Then, a realistic goal should be established for turn-away rate to maximize the use of precious hospital resources, along with an accompanying plan that engages with community partners to provide care for patients outside the inpatient setting.

- Build Flexible Units to Maximize Effective Unit Size. As a final step in planning, hospitals should consider a strategy to increase flexibility for each unit—which has become an even more paramount consideration following the COVID-19 pandemic. Building spaces adjacent to one another with different operating hours, such as perioperative prep spaces and ED positions, can allow some rooms to flex to serve different purposes depending on the time of day.

Another approach is making flexible units, built to high-acuity standards, that are capable of seeing multiple patient types, allowing rooms/units to flex between ICU and med/surg as necessary or be shut down in low census seasons and quickly brought back into operation when needed. This also effectively increases a unit’s size, decreasing the likelihood that patients of any one type will be turned away due to lack of beds. Figure 2 demonstrates the effect that unit size has on turn-away rate

Embracing Change

Updated planning standards can have multiple benefits for a hospital or health system, ultimately resulting in new facilities that meet the challenge of redefining the healthcare landscape. By dedicating the time and resources necessary to reimagining this future in each market, a hospital can set its strategic direction, engage internal stakeholders in redoubling their commitment to operational efficiency, and ensure the most efficient use of financial resources.

As the conventional hospital’s role in the healthcare landscape continues to evolve, hospital executives are faced with the unique and exciting challenge of reimagining the position of their facility within a shifting landscape, during or after the pandemic. The hospitals that rise to these challenges and redefine their services will be positioned to enhance the experience for staff and patients, as well as improve care delivery and quality for their communities for years to come.

Footnotes

-

1. Health Care Cost Institute, “2018 Health Care Cost and Utilization Report,” February 2020.

-

2. Ibid

-

3. As an example, the Washington state hospital bed planning standard has been unchanged since the early 1980s.

-

4. Kaiser Family Foundation. kff.org

-

5. Jones R. “Hospital Bed Occupancy Demystified” (2011), British Journal of Healthcare Management17(6): 242-248.