Despite the availability of best-practice guidelines, healthcare-associated infections remain a serious problem in the United States. It is estimated that 700,000 to 1.7 million people will contract an HAI every year1 and nearly 100,000 will die as a result,2 even though it is estimated that at least 50 percent of HAIs are preventable.3,4

However, intervention initiatives such as the surgical check list, Surgical Care Improvement Program, Project Joints from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and Comprehensive Unit Based Safety Program exist and have proven that standardized processes can meaningfully reduce the incidence of HAIs.5,6

Study findings highlighting the need of further standardizing of practices were presented at the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses Surgical Conference in March of this year. While there may be a general understanding among healthcare professionals that standardization improves outcomes, this study points out that there is considerable variation in skin preparation practices among hospitals and healthcare providers.7 Additionally, topical agents are not consistently applied according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved labeling. Therefore, the findings suggest a need to reeducate providers about the appropriate use and application of skin antiseptics to reduce or eliminate variability in pre-surgical skin antisepsis. This standardization may benefit both institutions and patients in the forms of less waste, fewer errors and better outcomes.

Discerning differences in skin antisepsis

The study presented at AORN examined 100 healthcare facilities enrolled in an audit evaluating skin antisepsis practices during the six-month period from Aug. 21, 2013 to Feb. 21, 2014. The facilities were dispersed geographically across the U.S. and included ambulatory surgical centers, small community hospitals and large academic centers of excellence. A team of clinical consultants captured data through interviews with nurses and by monitoring operating room procedures using a proprietary, automated iPad-based operating room audit tool provided by CareFusion Corp.

There were 775 observed procedures. Thirty-five percent were general surgery, 32 percent were orthopedic surgeries and 33 percent were a range of other surgeries.

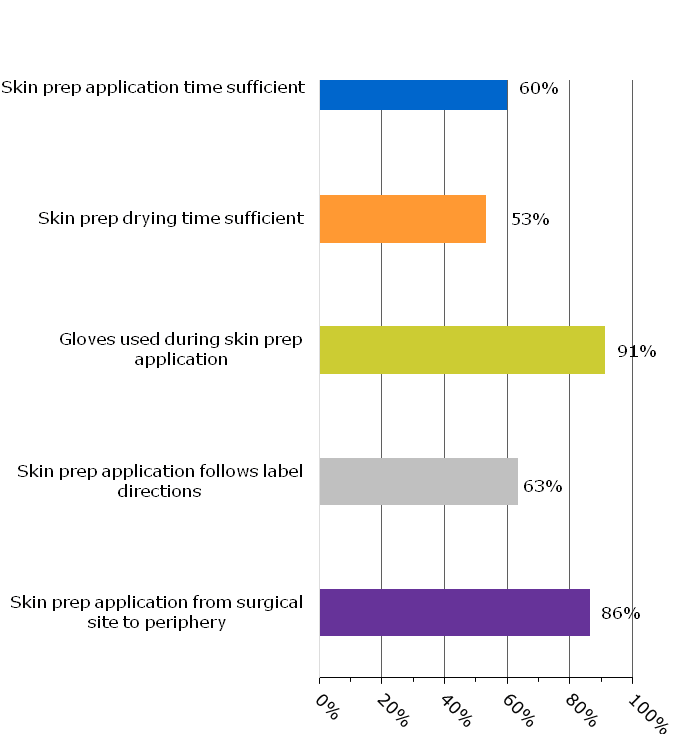

The data showed departures from standard preparation procedures occur often. For example, adequate skin preparation time and drying time — based on product label directions — were used only 60 percent and 53 percent of the time, respectively. Gloves were used only 91 percent of the time instead of universally. Antiseptic skin preparations were applied according to label directions only 63 percent of the time and were applied at the incision site and concentrically out from it 86 percent of the time (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Overview of Adherence to Standard Preparation Procedures

In addition, there was high variability in skin preparation application methods. Compliance with label directions was generally lowest (44 percent) among traditional agents such as PVP paint or scrub or gel preparations, which require concentric circles during application. Compliance was higher with povidone- and alcohol-containing agents (82 percent) and chlorhexidine gluconate preparations (65 percent), respectively (see Table 1).

Also, compliance with label application methods was greater with one-step preparations compared to two-step combination preparations (69 percent vs. 60 percent, respectively; see Table 2).

Table 1: Application method compliance with label direction among skin preps with different active agents

|

Surgical Skin Prep Products (Total # of Observations) |

Application Method Described in Approved Product Label Directions |

Percent of Time Applied Per Labeling Directions |

|

PVP Paint or Scrub or Gel (n=145) (10% PVP Paint, PVP-I Scrub & Paint, |

Concentric Circles |

44% |

|

PVP and Alcohol Containing Agents (n=87) (Iodine in Alcohol, e.g., 0.83% iodine/ |

Paint/Coating |

82% |

|

CHG-Based (n=531) (2% CHG in 70% Alcohol, |

Back & Forth Friction Strokes or Scrubbing |

65% |

Table 2: Application method compliance with label direction among combination skin preps

|

Surgical Skin Prep Products (Total # of Observations) |

Application Method Described in Approved Product Label Directions |

Percent of Time Applied Per |

|

1-Step Combination Prep (n=564) (2% CHG in 70% Alcohol, |

Varies (Back & Forth for 2% CHG in 70% Alcohol; Paint/Coating for Iodine in Alcohol) |

69% |

|

2-Step Combination Prep (n=85) (PVP Scrub & Paint) |

Concentric Circles |

60% |

Replace variability with standardization

In summary, this study demonstrated:

- Skin antiseptics are often applied without sufficient application time.

- Many skin preparation procedures are non-compliant with dry times.

- Gloves are not universally worn by clinicians during the application of skin preparations.

A significant percent of the time, surgical skin preparation solutions are improperly applied.

Therefore, there is an important need for improved education and training in preparation of the surgical site. Additionally, standardization of products could help improve compliance. For instance, other studies have shown that there is greater clinical efficacy, as well as time savings for one-step compared to two-step combination skin preparations.8 This study supports that the one-step products are also being used with greater compliance to label directions.

Perioperative nurses and other HCPs who are involved with skin antisepsis should play a large role in improving compliance and facilitating a culture of prevention. It would benefit institutions as well as patients to engage them in oversight and leadership, monitoring guidelines adherence, reporting discrepancies and teaching standardized methodology.

This study has two important limitations. First, it used a non-randomized convenience sample of healthcare facilities. Second, the audit only assessed processes of care and did not analyze patient outcomes. Measurable improvement in overall HAIs including infections at the site of the surgical incision will require attention to all of the clinical variables that can influence patient outcomes.8 All healthcare providers have the opportunity to support patient-centered quality initiatives by engaging in a dialogue to coordinate efforts across the points of care.

Dr. Donald Fry is adjunct professor of surgery at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and professor emeritus of surgery at the University of New Mexico. He has published over 400 journal articles and book chapters and is a past president of the Surgical Infection Society. Dr. Fry is on the speaker’s bureau for Merck and Co., and is a consultant to CareFusion, Ethicon and IrriMax corporations.

1 Magill SS. (2014) Multistate Point-Prevalence Survey of Health Care–Associated Infections. N Engl J Med; 370:1198-1208.

2 Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL Jr, et al. (2007) Estimating health care associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep 2007; 122:160-166.

3 Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. (2006) An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med;355(26):2725-2732.

4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Making health care safer: reducing bloodstream infections. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/VitalSigns/pdf/2011-03-vitalsigns.pdf June 3 2014.

5 Stulberg JJ, Delaney CP, Neuhauser DV, Aron DC, Fu P, Koroukian SM. (2010) Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and the association with postoperative infections. JAMA Jun 23;303(24):2479-85.

6 Bergs J, Hellings J, Cleemput I, et al. (2014) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of the World Health Organization surgical safety checklist on postoperative complications. Br J Surg Feb;101(3):150-8.

7 Xi H, Parsons V, Pearson L. Focus on quality care: An audit of surgical skin prep practices in U.S. hospitals. Poster presentation at: Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) Surgical Conference & Expo 2014. March 30 – April 2, 2014, Chicago, IL.

8 McDonald C, McGuane S, Thomas J, et al. (2010) A novel rapid and effective donor arm disinfection method. Transfusion Jan;50 (1):53-8.