Patients with cancer are often extremely ill, emotionally distressed and vulnerable. Medical oncologists routinely prescribe medications that are extraordinarily expensive, and patently unaffordable at full market price.

Oral chemotherapies are particularly problematic in that they are covered under Medicare Part D and listed in the highest tiers of drug formularies. As such, the patient is responsible large co-insurance payments (20% to 30% of the total costs) due to cost-shifting policies that have occurred over the past decade.1 The pharmaceutical industry and third-party payers engage in finger-pointing, whereby the manufacturers claim outrage that patients are forced to participate in the costs of the drugs, and payers claim that the prices are too high to fully cover. These financial hurdles have been shown to undermine drug access and patient adherence and have created a new literature on “financial toxicity”2. Out of pocket expenses for one drug could be over $20,000 to $30,000 per year, which is nearly half of the average annual household income in the US ($52,000 in 2013).3 One of the enabling mechanisms for the continual rise in prices is consumer silence. Through the efforts of their treating physicians and specialty pharmacies, many patients obtain financial assistance from charitable organizations to partially offset their copays. In turn, these wealthy charities are funded to levels of over $1 billion by the same pharmaceutical manufacturers that are driving up prices. Under the “cover” of charitable contributions, pharmaceutical companies can bypass the Anti-Kickback Statute, increase prices and revenue, and even earn tax credits.4 While the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and private insurers continue to finance the growing burden, consumers have not organized and provided sufficient vocal opposition due to the morbidity of their illness, dependency on the system, or frank unawareness.

Nationally, the cost of cancer drugs in the US was over $100 billion in 2015, and estimated to increase to $147 billion in 2018.5 Three key drivers of overall cancer care cost increases have been described: the percent increase in per-patient cost which is similar to the cost of care in the non-cancer population; site of service for chemotherapy shifting from physician offices to higher-cost hospital outpatient settings; and per-patient cost of chemotherapy drugs.6 This last driver is increasing at a much higher rate than the others. The public debate on cancer drug costs is a subset of the larger cost debate regarding all prescription drugs. This debate has generally centered-around the pros and cons of price regulation, which is thought to lower consumer costs in the short term, but possibly inhibit innovation due to decreased pharmaceutical revenues.7 Not to be overlooked or understated is the fact that 5 year cancer survival rates have improved by 20% over the past 20 years.8 Investment and innovation in cancer prevention and treatment have both contributed to this improvement; however the rising annual costs are not sustainable.

Determinants of drug prices

Oncology drug costs far exceed the average costs of non-cancer drugs. In the 1970’s the average cost of a month of therapy was $170, and by 2014 it was $10,000.9 Since 2012, 12 of 13 newly FDA-approved cancer drugs were priced above $100,000 annually.10 Additionally, some of these drugs must be given in combination to achieve maximal clinical response, such as immune-therapeutics. The FDA-approved combination of a PD-1 inhibitor (nivolumab) and a CTLA-4 inhibitor (ipilimumab) for metastatic melanoma given for one year is priced at approximately $250,000, which is more than the cost of an average US house.11 Immunotherapy utilization will dramatically increase over time, since the indications forimmunotherapy have expanded to more prevalent diseases such as lung cancer, and it is being actively studied in all other cancers. If research and development costs were the sole basis for drug pricing, then unit production costs should drop as the number of indications expand, and prices should drop as well, but this does not happen.12 Granted, the costs of R&D and company risk-taking are real and need to be considered and reconciled. The cost for the development of each new FDA-approved drug has been controversially calculated at $2.6 billion.13 Among other assumptions, this figure includes the costs of failure, wherein 90% of all drugs entering clinical trials do not achieve approval. However, pharmaceutical companies are often not the site of discovery of disruptive innovation, rather it is in the academic world where National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding generally supports such breakthroughs. It is estimated that 85% of cancer-related basic research is paid for through taxpayer dollars, whereas pharmaceutical companies spend only 1.3% of their revenues on basic research.14 Unfortunately, since 2003 there has been a 25% decrease in inflation-adjusted funding of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) budget, which was $5.2 billion in 2016.15 In the non-cancer realm, the blockbuster anti-HCV drug sofosbuvir (Harvoni) was initially priced at $94,000 for a 12 week course, whereas the production costs were in the range of $68 to $136.16 In comparison, this same 12 week course is sold in India for $300. To acquire the drug rights, Gilead had purchased the start-up biotechnology company that was created on the basis of the work of an NIH-funded professor at Emory. Gilead earned $12 billion in 2014, and the US government paid a large portion of that bill through CMS. Indeed there is a significant element of social injustice where Americans with cancer pay 50% to 100% more for the same brand-named drug than patients in other countries, and it is also their tax dollars that subsidize most of the basic research. The CMO for Express Scripts, the largest pharmacy benefit management organization in the US, supports the concept that some of the financial burden should be shifted to other countries.17

Drug prices may be influenced by a variety of factors besides R&D costs: competition within the pharmaceutical industry; corporate policies and obligations to investors; and governmental policies regarding competition and patent law. The latter policies are particularly problematic in that they have created anomalies in market forces which prevent them from naturally adjusting prices lower; instead prices are moving upward, limited only by what the market will bear. The two main anomalies in market forces that permit high prices are “protection from competition” and lack of “payer negotiating power.”18 Federal law grants both market- and patent-related exclusivity for brand drugs. These factors provide companies with monopoly rights for a defined period of time before a generic can be sold (5-7 years for small molecules and 12 years for biologics), and protects them from competition.19 It has been shown that the higher the number of manufacturers competing to produce equivalent generics, the lower the price will decline. For example, if more than five companies compete, the generic price can fall below 20% of brand price.20 As such, non-profit lobby organizations such as the National Coalition on Health Care have strongly supported policies that would facilitate approval of cheaper generic options, along with transparency in launch price and comparative effectiveness research to drive down prices.21 To extend the duration of their protected pricing, pharmaceutical companies may further prolong market exclusivity through “pay for delay” tactics; whereby generic manufactures are paid to delay production of their generic versions of the brand drug. In such cases, both the brand manufacturer and the would-be generic manufacturer share in the profits of an exclusive market position. The consumer (the patient) remains a victim of continued price escalation. It is this “government-protected monopoly rights for drug manufacturers” that appears to be the most important factor in in driving prices higher in the US.22

The second market anomaly is the lack of payer negotiating power. Specifically, some Federal agencies are prohibited by law from negotiating prices of drugs, as a result of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement and Modernization Act (MMA) of 2003.23 Despite the fact that Medicare accounts for 29% of drug expenditures in the US, CMS cannot leverage its purchasing power to negotiate for lower prices. Moreover, CMS is obligated to provide broad coverage, including all drugs in the oncology space. However, a precedent has been set, whereby another federal agency has a different set of rules. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is eligible for a rebate of at least 24% of the average selling price, and has the authority to exclude products from its formulary.24 California attempted to pass Proposition 19 in November 2016, whereby it would require State government programs to pay no more than the VHA. This was voted down after pharmaceutical groups spent tens of millions of dollars to defeat this ballot, arguing that it would limit patient access to innovative drugs.25

Additional inefficiencies in the private and public sectors also create an environment for high prices. From the governmental perspective, the Office of Generic Drugs at the FDA has had a slow application process for generic drugs, which may delay generic rollouts by years. From an industry perspective, there is an enormous redundancy in the clinical trials that study variations of the same basic drug, and fail to share data with each other. This has been seen for many years with next-in-class (“me-too”) drugs that target high profit market positions, such as cholesterol lowering agents, gastric proton pump inhibitors, and anti-hypertensives. A current example of this in the cancer market is immunotherapeutic checkpoint inhibitors. There are ~800 clinical trials that are testing various combinations of immunotherapy using a dozen different antibodies designed by a dozen different companies to inhibit the same target (PD-L1).26 Moreover, the dollars and research infrastructure that are utilized to generate me-too drugs create an opportunity cost whereby they are not being invested in new and yet unproved ideas.27 Clearly, the goal of pharmaceutical research is not only to strive to cure human cancer; rather to also partake in the profits of a highly lucrative market.

Solutions

The problems are clear, but solutions have been difficult to implement due to the large number of stakeholders, and the complexity and political nature of the issues surrounding drug pricing. The pharmaceutical lobby is powerful, the government is divided, third party payers have not been able or willing to negotiate, health system consolidation is driving overall costs higher, and patients continue to suffer the burden of collective inaction. Since deliberate governmental intervention such as the MMA had created the conditions for high prices, it is mandatory that it play a role in solving this issue. Public policy is starting to move towards decreasing the competitive protection afforded to brand drug producers. A recent Supreme Court decision voted 5 to 3 in favor of overturning an 11th Circuit court decision that a “reverse payment settlement”(type of “pay for delay”) does not violate anti-trust laws.28 The dissenting Supreme Court judges believe that the status quo position is acceptable, stating that the point of patents is to “grant limited monopolies as a way of encouraging innovation.”29 However, as the Harvoni example demonstrates, innovation primarily resides in academia. As such, this speaks loudly towards the benefits of a significant increase in the NIH &NCI budget, rather than dollars spent supporting massive drug manufacturer profits. Workman et al describe the need for new academic models of drug discovery and the infrastructure to support these programs.30 Academic drug discovery provides more freedom and incentive to engage in the types of challenges that would be seen as too risky by the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industry.31

Another potential solution is to expand the market and increase competition by importing drugs from outside of the US. In a bipartisan fashion, Senators have requested that HHS Secretary Tom Price allow importation of drugs from Canada.32 This came on the heels of yet another new drug being rolled out for muscular dystrophy at $89,000 per year in the US, versus $2,000 per year in Canada. PhRMA (Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America) representatives have been quick to state that such a policy would risk bringing counterfeit drugs across the border and bypass FDA regulatory standards. Of note, President Trump did support drug importation during his campaign, although it remains to be seen where he will finally land on this issue.33 PhRMA’s solutions for affordability and price sustainability include concepts based around the modernization of drug discovery, development and approval process.34 The first point concerns the improved efficiency of drug discovery at the scientific and organizational levels, which has been echoed by the scientific community.35 Moving away from the traditional randomized studies, and using new statistical methods and biomarkers to predict response will help to decrease financial costs, and unnecessary toxicities to the trial subjects.

The 340B pricing program developed by Congress in 1992 was intended to help offset expenses for vulnerable and uninsured patients at safety-net hospitals. Manufacturers are required to deeply discount medications for these facilities; and currently 6% of brand drugs are sold through this program creating a decline in revenue to the pharmaceutical industry of$18 billion. High reimbursements are especially concentrated in cancer medications where 340B pricing may represent up to 60% of hospital-based cancer center revenue.36 Essentially, enrolled cancer centers can purchase drugs for 30%-40% below average wholesale price (AWP) and are reimbursed from insurers at standard rates AWP+6% or higher. There is a valid concern on behalf of PhRMA that hospital systems have expanded the scope of 340B pricing programs beyond that of the original intent. For example, hospital systems have generally been able to also offer such discount pricing to community practices that they have acquired. Although there is a requirement for a certificate of need and an affiliation with a Disproportionate Share Hospital (DiSH), such expansions have spawned debate regarding the appropriateness of the broad-based application of this program to non-indigent populations. 340B pricing has clearly helped hospital-based cancer programs thrive and create substantial revenue for their parent health system. Moreover, many private practices have joined health systems to gain access to this special pricing as a survival tactic in an environment of declining reimbursement and increased regulation. Because 340B pricing creates revenue to help support a variety of ancillary services with in cancer cancers, the lack of such pricing would cause many centers to operate at a loss and force some to close. The reduction or dismantling of this program is not a solution by itself, and would only be possible as a component of a more comprehensive strategy.

The issue of CMS not having negotiating power regarding drug prices has been a topic of debate for many years. This barrier seems to be a unique situation that is found only in the US. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has been able to limit the approval of drugs based on value measurements below $60,000 quality adjusted life years (QALY). When value-based concepts like this have been raised in the US in the past, the public discourse has immediately turned towards “death panels.”37 Regardless, there is a movement towards value-based pricing that is gaining traction in a variety of clinical professional societies, since physicians are direct witnesses to the financial toxicities borne by their patients, and also must struggle through the bureaucracy to assist their patients.38 Moreover, since high drug prices often make them unaffordable and inaccessible to cancer patients, it has been suggested by some oncologists that the profession has a “moral obligation to advocate for affordable drugs.”39 ASCO (American Society of Clinical Oncology)40 and ESMO (European Society of Medical Oncology)41 are two of a group of professional societies that have developed value-based frameworks for evaluating new cancer drugs. In this context, value is defined as a measure of treatment benefits relative to cost.42 These frameworks consist of four parts relevant to the discussion of value and price: health outcomes; quality of clinical trial evidence; health benefit determination based on a formula or expert consensus; and value assessment as it relates benefits to cost. The frameworks move away from the world of FDA approval based solely on statistically significant p-values; rather outcomes such as overall survival and more meaningful endpoints are considered. For example, erlotinib (Tarceva) was approved for pancreas cancer in 2005 based on a statistically significant improvement in survival of only 12 days, and at a price of over $4,000 per month.43 Using these new frameworks, drugs such as this would not be approved at this price, if at all. In fact, value analysis using both the ASCO and ESMO models was applied to 37 FDA cancer drug approvals between 2000 and 2015.44 Not surprisingly, the authors found that many new FDA-approved cancer drugs do not have high clinical benefit, and that there is no relation between the price of drugs and benefit to patients and society.

Although promising as decision-making tools, the current iteration of value based models are limited by their patient-centric focus. Cost-effectiveness analysis focuses on the individual patient, and does not address the issue of overall budget impact in a system-wide fashion. For instance, the prevalence of chronic HCV is estimated to be 3 to 4 million cases.45 Although sofosbuvir (Harvoni) may be considered cost effective on an individual level by a QALY measure, due to the sheer number of cases, it is essentially unaffordable at its current price (3.5 million cases x $94,000/case = $332 billion) at a national level.46 Regardless of the fact that these frameworks require further modeling and refinement, the issue of implementation is challenging, since various stakeholders perceive value and risk tolerance from different perspectives. There is no one-size-fits-all solution, and future iterations must be adaptable.

Conclusion

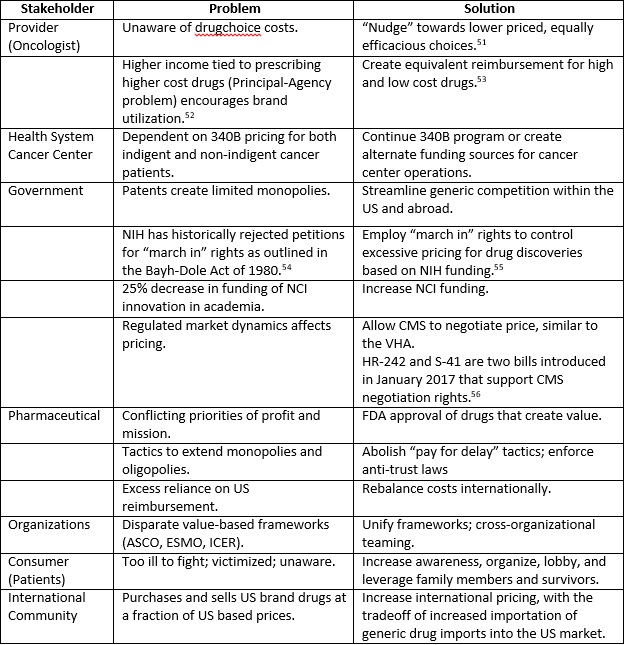

Over the past 15 years, much has been written and discussed regarding the increasing costs of drugs, and the concerns and issues that existed then remain intact.47 The unsustainable pricing epidemic has sustained. The solution to address the costs of cancer drugs in the US is a multi-pronged strategy, with all relevant stakeholders at the negotiation table. Along with the aforementioned, additional impactful ideas are tabulated (Appendix A). As in any interest-based negotiation, all participants must actively listen to the perspectives and priorities of the other parties, find common ground and create new solutions that do not currently exist.48 Cancer is narrowly in second place to heart disease as the most common cause of death in the US, and a much more common cause of death in young individuals.49 As such, many of us are or will become a patient with cancer, or become a family member or friend of a cancer patient. It is with this perspective and the realization of our interdependencies that we must enter into negotiation. Innovative pharmaceutical companies should be permitted and encouraged to acquire a reasonable profit from the sale of drugs that create value to the patient and to society. The US government must create an environment where market forces are restored to determine that that balance, and always remain vigilant for unintended consequences from its actions. To catalyze the change process, consumers must organize and advocate for themselves, apply political pressure, and demand just and equitable pricing.50

1 (Kaiser, 2015)

2 (O'Conner, et al., 2016)

3 (Kantarjian & Rajkumar, 2015), p 501

4 (Elgin & Langreth, 2016); see (Furrow, et al., 2013) for Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS)42 USC §1320a–7b

5 (Burkholder, 2015), p 842

6 (Fitch, et al., 2016), p 3

7 (RAND, 2008)

8 (Fitch, et al., 2016), p 5

9 (Saltz, 2016)

10 (Workman, et al., 2017), p 579

11 (Workman, et al., 2017)

12 Ibid, p 579

13 (Avorn, 2015)

14 (Kantarjian & Rajkumar, 2015), p 502

15 (NCI, 2017)

16 (Sachs, 2015)

17 (Wieczner, 2016)

18 (Kesselheim, et al., 2016), p 860

19 Ibid, p 861

20 (FDA, 2015)

21 (National Coalition on Healthcare, 2016)

22 (Lupkin, 2016)

23 (Workman, et al., 2017), p 579

24 (Kesselheim, et al., 2016), p 862

25 (Meyer, 2016), p 15

26 (Workman, et al., 2017), p 580

27 (Bach, 2014)

28 (Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis, Inc., 2013), p 5

29 Ibid, p 26

30 (Workman, et al., 2017)

31 Ibid

32 (Dickson, 2017)

33 (Meyer, 2016), p 13

34 (PhRMA, 2017)

35 (Workman, et al., 2017)

36 (PhRMA, 2017), p 9

37 (Meyer, 2016), p 14

38 (Hunter, et al., 2016)

39 (Kantarjian & Rajkumar, 2015), p 501

40 (Schnipper, et al., 2015)

41 (Cherny, et al., 2015)

42 (Chandra, et al., 2016), p 2069

43 (CBSNews, 2010)

44 (Vivot, et al., 2017)

45 (CDC, 2017)

46 (Neumann & Cohen, 2015)

47 (Carey & Barrett, 2001); price of imatinib (Gleevec) was $26,000/year in 2001 and $140,000/year in 2016

48 (Marcus, et al., 2011)

49 (Pathak, 2016)

50 (O'Donell & Shesgreen, 2017)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arno, P. & Davis, M., 2001. Why Don’t We Enforce Existing Drug Price Controls? The Unrecognized and Unenforced Reasonable Pricing Requirements Imposed upon Patents Deriving in Whole or in Part from Federally Funded Research. Tulane Law Review, pp. 631-693.

Avorn, J., 2015. The $2.6 Billion Pill — Methodologic and Policy Considerations. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(20), pp. 1877-1879.

Bach, P., 2014. Could High Drug Prices Be Bad For Innovation?. [Online]

Available at: http://www.forbes.com/sites/matthewherper/2014/10/23/could-high-drug-prices-be-bad-for-innovation/#65758b028135

[Accessed 11 February 2017].

Burkholder, R., 2015. Pricing and Value of Cancer Drugs. JAMA Oncology, September, 1(6), pp. 842-843.

Carey, J. & Barrett, A., 2001. Bloomberg Businessweek. [Online]

Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2001-12-09/drug-prices-whats-fair

[Accessed 25 March 2017].

CBSNews, 2010. CBS News. [Online]

Available at: http://www.cbsnews.com/news/93000-cancer-drug-how-much-is-a-life-worth/

[Accessed 18 February 2017].

CDC, 2017. Hepatitis C FAQs for Health Professionals. [Online]

Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#a5

[Accessed 26 February 2017].

Chandra, A., Shafrin, J. & Dhawan, R., 2016. Utility of Cancer Value Frameworks for Patients, Payers,and Physicians. JAMA, 315(19), pp. 2069-2070.

Cherny, N. et al., 2015. A standardised, generic, validated approach to stratify the magnitude of clinical benefit that can be anticipated from anti-cancer therapies:the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). Annals of Oncology, 26(8), p. 1547–1573.

Dickson, V., 2017. Senators want Price to import cheap drugs from Canada. [Online]

Available at: http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20170215/NEWS/170219932?utm_source=modernhealthcare&utm_medium=email&utm_content=20170215-NEWS-170219932&utm_campaign=dose

[Accessed 16 February 2017].

Elgin, B. & Langreth, R., 2016. How Big Pharma Uses Charity Programs to Cover for Drug Price Hikes. Bloomberg Businessweek, 23 May, pp. 1-10.

Epstein, A. & Johnson, S., 2012. Physician response to financial incentives when choosing drugs to treat breast cancer. Int J Health Care Finance and Economics, 12(4), pp. 285-302.

FDA, 2015. Generic Competition and Drug Prices. [Online]

Available at: http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/ucm129385.htm

[Accessed 12 February 2017].

Federal Trade Commission v. Actavis, Inc. (2013) Supreme Court.

Fitch, K., Pelizzari, P. & Pyenson, B., 2016. Cost Drivers of Cancer Care: A Retrospective Analysis of Medicare and Commercially Insured Population Claim Data 2004-2014, Seattle: Milliman.

Furrow, B. et al., 2013. FRAUD AND ABUSE. In: THE LAW OF HEALTH CARE ORGANIZATION AND FINANCE. St Paul, Minnesota: West Academic Publishing, pp. 770-776.

Hunter, W., Zhang, C., Hesson, A. & Davis, J., 2016. What Strategies Do Physicians and Patients Discuss to Reduce Out-of-Pocket Costs? Analysis of Cost-Saving Strategies in 1,755 Outpatient Clinic Visits. Medical Decision Making, October, Volume October, pp. 900-910.

Kaiser, 2015. Employer Health Benefits, s.l.: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Kantarjian, H. & Rajkumar, V., 2015. Why are Cancer Drugs so Expensive in the United States, and What are the Solutions?. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(4), pp. 500-502.

Kesselheim, A., Avorn, J. & Sarpatwari, A., 2016. The High Cost of Prescription Drugs in the United States: Origins and Prospects for Reform. JAMA, 316(8), pp. 858-867.

Lupkin, S., 2016. 5 Reasons Prescription Drug Prices Are So High in the U.S.. [Online]

Available at: http://time.com/money/4462919/prescription-drug-prices-too-high/

[Accessed 11 February 2017].

Mailankody, S. & Prasad, V., 2016. Implications of Proposed Medicare Reforms to Counteract High Cancer Drug Prices. JAMA Oncology, 316(3), pp. 271-272.

Marcus, L., Dorn, B. & McNulty, E., 2011. Renegotiating Healthcare. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Meyer, H., 2016. No quick fix for Rx price spikes. Modern Healthcare, 3 October, pp. 13-16.

National Coalition on Healthcare, 2016. Policy and Advocacy Overview. [Online]

Available at: http://www.nchc.org/policy/

[Accessed 11 February 2017].

NCI, 2017. NCI Budget and Appropriations. [Online]

Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/budget

[Accessed 19 February 2017].

Neumann, P. & Cohen, J., 2015. Measuring the Value of Prescription Drugs. The New England Journal of Medicine, 373(27), pp. 2595-2596.

O'Conner, J., Kircher, S. & deSouza, J., 2016. Financial Toxicity in Cancer Care. The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, 14(3), pp. 101-106.

O'Donell, J. & Shesgreen, D., 2017. USA Today. [Online]

Available at: http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/02/22/new-patient-group-focuses-drug-prices-amid-bipartisan-concern/98168146/

[Accessed 25 March 2017].

Pathak, E., 2016. Is Heart Disease or Cancer the Leading Cause of Death in United States Women?. Womens Health Issues, December, 26(6), pp. 589-594.

PhRMA, 2017. Policy Solutions: Delivering Innovative Treatments to Patients. [Online]

[Accessed 16 February 2017].

RAND, 2008. Regulating Drug Prices U.S. Policy Alternatives in a Global Context, s.l.: Rand Corporation.

Sachs, J., 2015. The Drug that is Bankrupting America. [Online]

Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jeffrey-sachs/the-drug-that-is-bankrupt_b_6692340.html

[Accessed 11 February 2017].

Saltz, L., 2016. Perspectives on Cost and Value in Cancer Care. JAMA Oncology, 2(1), pp. 19-21.

Schnipper, L., Davidson, N. & Davidson, D., 2015. American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement: A Conceptual Framework to Assess the Value of Cancer Treatment Options. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(23), pp. 2563-2577.

Treasure, C., Avorn, J. & Kesselheim, A., 2015. Do March-In Rights Ensure Access to Medical Products Arising From Federally Funded Research? A Qualitative Study. The Milbank Quarterly, 93(4), pp. 761-787.

US Congress, 2017. Congress.gov. [Online]

Available at: https://www.congress.gov/search?q={"congress":"115","source":"legislation","search":"drug and price"}&searchResultViewType=expanded

Vivot, A. et al., 2017. Clinical Benefit, Price and Approval Characteristics of FDA-approved New Drugs for Treating Advanced Solid Cancer. Annals of Oncology, Volume [published ahead of print].

Wieczner, J., 2016. Why Express Scripts CMO Thinks Drug Price Regulation Is a “Bad Idea”. [Online]

Available at: http://fortune.com/2016/11/02/express-scripts-drug-price-regulation/

[Accessed 11 February 2017].

Workman, P., Draetta, G., Schellens, J. & Bernards, R., 2017. How Much Longer Will We Put Up With $100000 Cancer Drugs. Cell, Volume 168, pp. 579-583.

The views, opinions and positions expressed within these guest posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of Becker's Hospital Review/Becker's Healthcare. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.