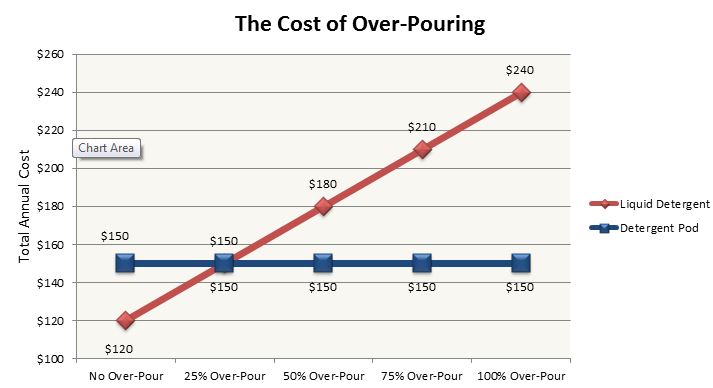

Each year, 600 loads of laundry are performed by the average American household. There aren't many steps to performing a well-washed load of laundry, yet more than half of households inaccurately perform the most critical task by over-pouring laundry detergent.

Historically, manufacturers saw an increase in detergent sales with each new increased level of concentrated detergent. In 2008, laundry detergent sales rose 5 percent following the release of higher-concentrated detergents. These higher-concentrated detergents served as a convenience for consumers, allowing manufacturers to charge more per load. However, putting more concentrates in detergents didn't equate to consumers pouring less. Enter detergent pods in 2012.

Detergent pods are a highly concentrated, single-load detergent packed into a water-soluble membrane. Over-pouring a pod is impossible, as the pod removes the task of pouring altogether. Suddenly, Americans had access to the perfect amount of laundry detergent per load without the threat of over-pouring. Being a product of convenience, manufacturers priced the product at 25 to 75 percent more per load.

Yet, despite historical concentrating trends and a higher price product, sales of detergent fell 2.1 percent in the year following pods' release. Consumers finally began using appropriate amounts of detergent per load.

Value analysis in healthcare can learn a lot from detergent pods. Saving money isn't about choosing the most concentrated product or buying the cheapest, generic brand of detergent possible. The savings are in the pour!

Nothing in the healthcare commodity world will reduce costs more than choosing and using products more appropriately.

There is a hospital in New York that noticed it was spending large sums of money on Foley catheters. Determined to cut costs, the hospital converted to a lower-cost manufacturer, reaping the benefits of a 14 percent cost reduction. Fourteen percent is nothing to balk at, but costs remained high despite price benchmarks showing favorable results. Hiding in their data was the answer to why Foley catheter costs were so high. Foley catheter usage at this hospital was twice that of other hospitals, and further digging revealed that practice was to blame. Clinical practice was that the clinician often pulled two catheters for every insertion. Having an extra on hand was easier than having to disrupt the sterile field to obtain a new one when the clinician had difficulty inserting on the first attempt. Collaboration among other hospitals with lower Foley catheter usage showed they required two clinicians to perform catheter insertion, which reduced insertion difficulty and catheter-associated urinary tract infection incidence. Once this hospital implemented these protocols, their first attempt success rates increased and the need for two catheters for one insertion became obsolete. The change resulted in a 50 percent cost reduction, blowing the previous 14 percent out of the water!

This is a classic incidence of over-pouring, and it's happening every day in hospitals. Two catheters are selected when only one is used, three instant ice packs are given when a reusable ice bag serves the same purpose, saline bags are pre-spiked and thrown out, or slippers are given on admission even though the patient is already wearing a pair; the list goes on and on and on.

With so many instances of over-pouring in healthcare, facilities need help determining where to start implementing healthcare's version of detergent pods. Hospitals need not turn to consultants but instead to analytics companies that enhance the resources healthcare providers already have. Choosing an analytics company to help with this effort can be difficult, so it's important to look for one that digs past category-level benchmarks, providing better insight into product characteristics and variables. Without this, a hospital might make the mistake of converting urinary catheters to reduce price when the problem really lies with the use of a specific treated Foley catheter tray. Also, hospitals should choose a company that's focused on the end user. These are the people who ultimately are responsible for implementing and maintaining change, so make sure data results and supporting documents are interpretable to them. Lastly, go with a company that provides clear next steps to implement the conclusions drawn from the data. Too many companies provide synopses and not solutions, informing the user of what happened rather than what to do about it.

All hospitals have their fair share of dirty laundry, but to save money, they need not change detergent, limit loads or stop the spin cycles altogether. Instead, just trust in the power of pods and stop pouring away the product.

Lindsey Crea is the director of the Utilization Program and has been with Blue.Point Supply Chain Solutions since 2012. She is responsible for the day to day operations and development of the utilization program. The utilization program targets savings opportunities, outside of price points and contracts that focus on clinical product selection and practice.

Prior to working at Blue.Point, Lindsey worked clinically in an acute care setting. She has a master's degree in health informatics and management from the University of Massachusetts, a bachelor's degree in medical laboratory science from the University of New Hampshire and is a medical laboratory scientist as certified by the American Society of Clinical Pathologists.

More Articles on Supply Chain:

MD Buyline: 5 Insights on Device Recalls

Compumedics USA Enters Preferred Vendor Agreement With HealthTrust

10 Trends in Hospital Supply Chain Management