A gathering storm of rising malpractice costs, payment penalties, new quality frameworks, patient safety report cards and media attention may be leaving healthcare providers with little choice but to act to prevent the medical error known as a retained surgical sponge.

An overwhelming amount of clinical evidence shows that manual counting of sponges — even when carried out under evidence-based guidelines — often fails due to human error and other factors, resulting in sponges being left inside patients after surgery.

The National Quality Forum describes 28 "never events," medical errors that should never occur because they are entirely preventable, and the occurrence of a retained surgical sponge is one such event. Clearly, any never event can have a negative financial and reputational impact on a hospital, but can the impact be quantified?

An analysis of government records, clinical studies and two major databases of malpractice claims suggests that a single case of a retained sponge can cost a hospital and the surgeon well over half a million dollars in indemnity payout and legal fees — far more than earlier estimates. With the effect of payment reforms added in, the cost to a hospital is even higher.

The nature of the problem

Surgical sponges range from small gauze pads to full towels, some measuring more than a square foot. Retained sponges are difficult to diagnose due to vague, inconsistent symptoms and unclear images from X-rays. Sometimes they can present as a mass in the body or as a bowel tumor.

Left in the abdomen — the most likely location for a retained sponge — they can wreak incredible havoc. Sponges can wrap around and perforate the colon, fill the gap between organs and cause hemorrhaging and infections. Surgery to remove them often involves taking out entire sections of the colon, permanently leaving some patients with bags on their abdomens to collect waste. Rarely, a retained sponge can cause death, as in the case of Geraldine Nicholson of Lumber Bridge, N.C.

Prior to her death, Ms. Nicholson spent a year in a hospital with complications after surgery to remove cancerous tissue in her rectum and colon. A surgical sponge measuring more than a square foot was left inside her abdominal cavity, and it stayed there for 10 weeks. The sponge created infections and other complications that disqualified Nicholson from receiving cancer treatment that could have saved her life, testimony at the malpractice trial of her surgeon, Arleen Kaye Thom, MD, showed. Dr. Thom allegedly failed to order a sponge count before concluding the surgery. A jury agreed that Dr. Thom acted with negligence, and in October 2012 a judge ordered her to pay $5.1 million to Nicholson's estate and $750,000 to her husband.

An avoidable problem

"These events are relatively rare, but they are serious and they are persistent, despite readily available technologies that make retained sponges a nearly totally avoidable problem," says Atul Gawande, MD, a Harvard public health researcher, author and surgeon at Boston's Brigham and Women's Hospital. The bar-coded sponges from SurgiCount Medical, in use at Dr. Gawande's hospital, assist nurses in accounting for all items used in a procedure prior to closing up a patient. Another common technology in use is radiofrequency-tagged sponges.

"Each case is an event that has happened to a human being, so it is incredibly important," says Ronald Wyatt, MD, medical director of The Joint Commission. Retained surgical items are often hidden from victims as well. As a young medical student, Dr. Wyatt witnessed a surgeon remove a mass from a patient's wrist. "When we removed mass and found a sheared off catheter in the middle of it, the doctor said, 'Let's just tell him it was a ganglion cyst.' This kind of deception has gone on forever and still goes on today."

The true incidence of retained surgical items, including sponges, is not precisely known, but most researchers now cite as benchmarks two large-scale studies, a four-year project at Mayo Clinic and the other at five large teaching institutions. The Mayo study found an incidence of one in 5,500 operations. The multicenter study estimated an overall incidence of one in 6,975 cases.

Examining the results of more than two dozen studies, it appears likely that roughly two thirds of all retained surgical items are sponges.

Despite national practice standards related to sponge counting, studies show these protocols are routinely ignored, and in any case are insufficient.

In the multicenter study cited above, among the 55 of 59 retained surgical sponges, operations proceeded to completion in 10 instances, despite at least one team member being aware of an incorrect sponge count. About half of the retained sponges were missed by the X-ray reading.

One effort to incentivize technology

Through Dr. Gawande's efforts, CRICO, the medical malpractice insurer for Partners Healthcare, an 11-hospital system affiliated with Harvard Medical School, has offered to fund the adoption of sponge-counting technology at the hospitals.

"CRICO will literally cut a check for $75,000 to pay for the first year of capital costs for switching to an automated sponge counting technology," Dr. Gawande said. "This is technology that has been around for several years," and with it you can get close to zero events, he said.

Dr. Gawande runs the Partners patient safety committee, made up of the hospitals' chiefs of surgery. At a recent meeting, he won the endorsement of every member to adopt the technology.

Malpractice risk

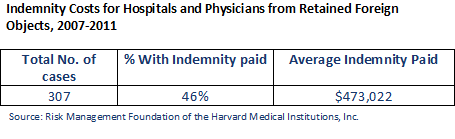

For this article, the Risk Management Foundation of the Harvard Medical Institutions reviewed its database of thousands of malpractice closed claims. It found that the average indemnity payout for a claim involving a retained surgical item for hospitals and physicians was approximately $473,000 from 2007-2011. For cases involving permanent major damage to a patient, the average claim was $2 million.

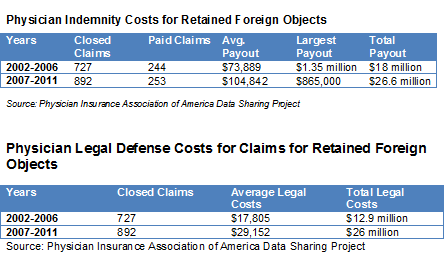

The Physician Insurers Association of America was asked to examine its Data Sharing Project — the largest physician malpractice database. For the same period, the average physician-only indemnity payout was $105,000.

The Physician Insurers Association of America was asked to examine its Data Sharing Project — the largest physician malpractice database. For the same period, the average physician-only indemnity payout was $105,000.

Defense costs for malpractice cases have been rising faster than claims. According to the Insurance Information Institute, approximately 61 percent of medical professional liability insurers' total incurred losses was spent on defense costs and cost containment expenses in 2010, compared to approximately 40 percent in 2000.

Based on all of this data, a calculation was made of the malpractice impact per case of a retained surgical item in the U.S. annually. This calculation is based on the CDC's National Hospital Discharge Survey, which showed 34.1 million inpatient procedures for which a retained sponge was possible (excluding eye surgery, CT scans, etc.); the incidence of retained surgical items found in the Mayo study; the average indemnity payout from the Harvard database; and the legal costs in inflation-adjusted 2013 dollars. It shows that a retained surgical item adds $94.50 to the cost of a relevant surgery — roughly nine times the cost of sponge-counting technology.

Government penalties

Though there is considerable debate about the effect of government and commercial insurer "no-pay rules" for the added cost of repairing the damage wreaked by retained sponges, it seems likely that some hospitals simply absorb those costs. An inflation-adjusted 2007 estimate from CMS finds the added cost of a second surgery and follow-up care for a retained surgical item is $77,512.

State Medicaid payment is also withheld for the added care of a second surgery. More states are publicizing hospitals' track records on medical errors. California has taken the next step: Since 2010 the state has fined hospitals a total of $1.8 million over 30 cases of retained sponges.

The accountable care effect

New payment and organizations created by the PPACA of 2010 may incentivize healthcare providers to ensure that retained surgical sponges are consigned to history.

The accountable care organization replaces the idea of reimbursing individual physicians and hospitals by procedure with a lump-sum payment to clinicians working as a formal ACO team. Under the terms of the PPACA, a Medicare ACO agrees to be responsible for all the care needs of a group of patients and to be paid based on those patients' health outcomes, satisfaction and costs. Under ACOs, hospitals are going to be on the hook for all complications.

"The demand side push for healthcare system transformation has to be there or else it ain’t gonna happen," says Andrew Webber, president and CEO of the National Business Coalition on Health, a consortium of 54 business health coalitions across the United States representing over 7,000 employers and approximately 25 million employees and their dependents. "It is foundational in our mind. We can point the finger at ourselves for not being demanding enough previously in using the payment system so that providers are at risk for complications such as [retained surgical items]."

A focus on reputation

The damage to a hospital's reputation from publicity surrounding a retained sponge is harder to calculate in dollar figures, but it is surely considerable. USA Today in March published a lengthy investigative report on retained sponges, naming names of victims, physicians and hospitals.

Among many other assessments of hospital quality, the release of a patient safety report card by the employer-based Leapfrog Group in the spring of 2012 attracted the most national attention. The effort, which awards hospitals letter grades from A to F, is based on a methodology created by a panel that included Ashish Jha of Harvard, Arnold Milstein of Stanford, Peter Pronovost of Johns Hopkins and others. Retained surgical items make up 6 percent of the total score; Leapfrog's is the only consumer hospital safety assessment project that includes them.

In May 2013 Leapfrog released its latest round of safety scores, and nearly three-quarters of hospitals maintained the same letter grade they received in November 2012, when the organization issued its last update. Of the 2,514 hospitals covered in the most recent update, 780 received an A, 638 a B, 932 a C, 148 a D and 16 an F.

"Our board considers the Hospital Safety Score the most important patient safety initiative we have ever done, and we are full speed ahead on this," says Leah Binder, Leapfrog's CEO. "We got hospitals' attention, but more importantly, we got consumers' attention. We have had tens of thousands of pieces written about the safety score."

Perhaps more importantly, Leapfrog has had hundreds of calls from hospitals that have had low safety scores, want to understand the score better and learn how they can improve.

"It is very clear that for a hospital institution, community reputation is critically important to their branding, to their image, and they will respond, particularly if that information is transparent enough and out in the open," Mr. Webber added.

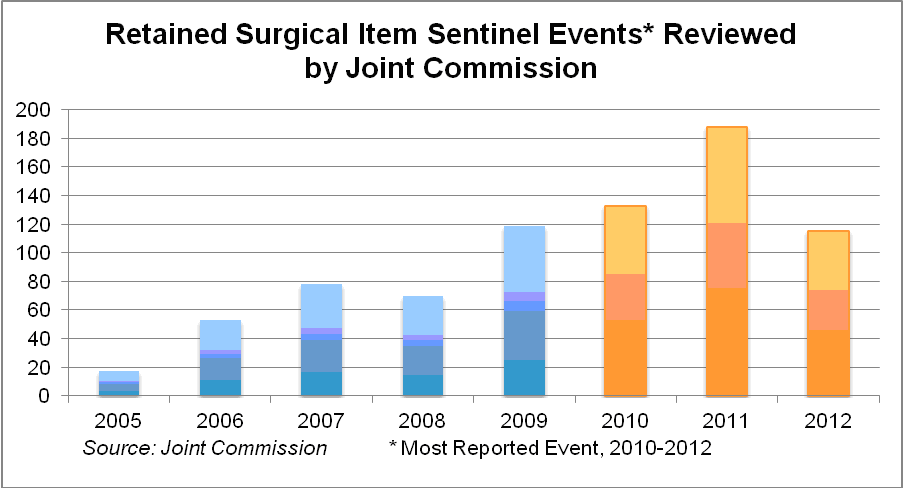

Meanwhile, The Joint Commission is planning to publish a Sentinel Event Alert on retained surgical items, which for three years have been the most reported adverse event to the commission.

"We know that the actual number of (retained surgical items) is vastly underreported, likely not much more than 10 percent of the events that actually occur," the commission's Dr. Wyatt says. "Most hospitals are just at the starting point of working on and improving the reliability of processes, and this is one of them."

The alert will dig into root causes of retained items, including failure of leadership, lack of good processes, poor communication among the surgical team and other human factors.

The new focus on retained surgical items has struck a nerve. An Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses survey in June 2013 found that retained surgical items were the No. 2 patient safety concern of members, right behind wrong site/wrong patient surgeries. Sixty-one percent of the nurses who were surveyed identified preventing retained items as a high priority.

With health reform's focus on high-quality, safe and patient-centered care — as well as new healthcare delivery models such as accountable care organizations that put providers at risk for both cost and quality — an easily preventable medical error such as a retained sponge is harder to justify than ever before.

Todd Sloane is 30-year veteran of journalism and communications and spent 14 years as a top editor at Modern Healthcare.