Every year 130.4 million patients visit emergency departments across the United States, making the ED a key patient access point for hospitals.

Of those visits: 37.2 million are injury-related visits, 12.2 million result in hospital admissions, 1.5 million result in admissions to critical care units, and 2.2 percent result in ED transfers to psychiatric or other hospitals for care. 1

Heidi Gartland, vice president of government relations at University Hospitals, said it well: "Emergency rooms are the places patients show up, [and that's] not the most efficient healthcare dollar expenditure." 2

As the statistics show, from 1999 through 2009 – prior to the Affordable Care Act – the number of visits to emergency departments increased 32 percent, resulting in overcrowded EDs, long wait times and ballooning hospital bad debt due to high numbers of uninsured patients showing up at the ED for care. The hope of many hospitals was that the ACA would help mitigate many of those issues. While many hospitals are working hard to keep wait times short, using online check-in, split-flow patient triage models and separate EDs for pediatric or geriatric patients, the National Center for Health Statistics indicates that only 29.8 percent of U.S. hospitals serve ED patients in fewer than 15 minutes. The vast majority of hospitals within the United States continue to fall well-below better performance. 1

There are many factors keeping hospitals from hitting their operational and financial sweet spots, but in our consulting experience, three areas consistently surface as barriers: 1) ineffective use of data and technology, 2) a culture averse to change and 3) clinical and operational practice variation. This article will discuss all three in more depth.

Data and Technology

It is rare for patients these days to enter an emergency department without some form of technology in their hand or pocket. Yet many U.S. emergency departments still do not use data or technology to their fullest potential or act on the data collected.

A survey completed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in Rockville, MD [Grant No. 5 R01 HS013099] of 99 emergency departments in 23 states validated that to be the case. The researchers reported that 99 percent of the respondents indicated they used some form of technology applications in their ED. However, when the researchers dug deeper, they learned the hospitals were simply using technology as a means to relay information from one place or person to another for patient tracking (74 percent), ordering laboratory tests (62 percent) or for communicating test results (92 percent), laboratory results (97 percent) and radiology reports (99 percent). 3

Only a small portion of the surveyed hospitals indicated they had fully adopted technological applications such as electronic medication ordering (38 percent) or adverse medication cross-reaction warnings (13 percent). Only 20 percent indicated they used bar-coding technology in their EDs, though this tool has been available for decades. 3

But barriers such as cost and difficulty of implementation have impeded many U.S. hospitals from taking advantage of this benefit.4 Many hospitals have upgraded their technology but do not use it appropriately or to the fullest extent. We encountered one such example while working with a Level 1 trauma center outside a metropolitan city.

This major teaching hospital utilized an electronic ED patient bed registration system and smartphone communication technology to engage EMS and physicians in decision making. But they failed to use one of the most basic tools in their EPIC arsenal – electronic flags. These flags, if routinely "flipped" by providers alert, staff when a patient is ready to go to the next step in care, such as imaging, lab or discharge. As a result, patients sat disgruntled in waiting rooms as the clock ticked away and providers wasted time following up.

This same ED collected standard ED quality metrics like door-to-doctor minutes, length-of-stay minutes and door-to-discharge times but never analyzed the trends the data showed or took action, rendering the benchmarks essentially useless.

If other hospitals across the country are making these same basic day-to-day mistakes, could this be a reason for why only 29.8 percent of U.S. hospitals serve ED patients in fewer than 15 minutes? 1

As Dr. Regan Henry, PhD, Healthcare Architect and Research Director at E4H Environments for Health Architecture, points out in his February 13, 2017 article published in Becker's Hospital Review, there are at least seven technological avenues currently available which, if utilized consistently and properly, would revolutionize the way emergency departments treat and care for patients.

1) Miniaturization of imaging and diagnostic equipment, (e.g. bedside I-STAT blood testing),

2) Exam room telemedicine smart TVs ,

3) Handheld mobile tablets with real-time accessibility to EMRs,

4) Patient flow software to identify available beds by specialty,

5) On-line patient check in or free-standing kiosks,

6) Real-time patient locating systems (RFID) allowing nurses to know exactly where ED patients are at all times, and

7) Use of lean principles, to identify ED waste by standardizing work processes and ensure reproducible and predictable outcomes. 5

So why are some EDs in the United States not taking full advantage of these innovations? To be fair some are. However, many others are not innovating for basic reasons such as lack of resources and cultural norms rendering them averse to change.

Staffing, Leadership and Cultural Norms

As the old saying goes, "you can lead a horse to water, but you can't make him drink." These words are applicable to the Level 1 trauma center example previously described. This ED, in addition to not using technology effectively, had cultural blind spots and fear of change. In short, they were doing what they always had done and getting results they did not want but didn't know how to correct.

On average a busy Level 1 trauma center can see patient swings of up to 40 percent from hour to hour. So when it comes to staffing an ED effectively for peak performance, where do you start?

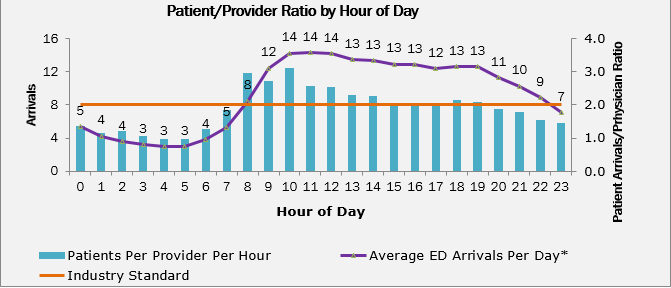

Based on the premise that there are 8,760 hours in a year and the ED is open every one of those hours, the appropriate ratio of provider to patients per hour should run around 1.8 to 2.8 patients per provider per hour.6

Kirk B. Jensen, M.D., MBA, a faculty member of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in Boston and chair of IHI's collaborative on Improving Flow in the Acute Care Setting and Operational and Clinical Improvement in the ED, believes when matching your staffing capabilities or capacity to demand, all EDs reach an inflection point. Dr. Jensen believes once an ED reaches 2.1 or 2.2 patients on average per hour, per provider, it is time to take a critical look at the ED provider staffing patterns. This involves considering both provider proficiency and the use of a mix of physician provider-to-patient ratios versus mid-level provider-to-patient ratios. 6

Figure 1 below illustrates how one Level 1 trauma center has gone beyond its inflection point. The center averages as high as 12 to 14 patients per hour per provider during peak flow times. As you can see, the hospital collected data. What you don't see is they were not acting on what the data was revealing. This ED's day-to-day operations were terribly dysfunctional. No one was really leading or managing the department, and patients were paying the price.

The Chief of Emergency Medicine and physician leaders mistrusted the nursing leaders and managers. The ED business managers collected the operational data illustrated in Figure 1 but failed to share it, and the managers never asked for the data.

Figure 1: Sample Patient Arrival Patterns and Provider Ratios by Hour of Day

When our team was called in, we discovered Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores in the 20th percentile, ESI Level 5 patients walking in but immediately being put on stretchers (the hospital norm), no real effective patient triage models and patient length of stays for admitted and treat/release patients on average 9.2 and 12.1 hours, respectively. To say this ED was not operating efficiently would be an understatement. The hospital's staffing problems fell squarely into the areas Dr. Jensen alluded to:

The ED saw no need to use mid-level providers in their triage areas, even though on average 30 percent of all ED patients can be easily seen and independently treated by mid-level providers (e.g. physician assistants or nurse practitioners) to improve patient flow and throughput. 6

They had not embraced common ED split-flow patient throughput models due to their cultural norm of placing every single ED patient on a stretcher prior to being seen by a provider.

These kinds of cultural inflexibility, lack of day-to-day management and outlier staffing protocols makes one wonder: Just how often are other EDs around the country experiencing overcrowding simply because they are doing what they have always done? Creating a culture for change is hard work, but doing what you've always done is a recipe for disaster.

Clinical Variation and Quality

In February 2014, 45 emergency medicine leaders from around the United States convened in Las Vegas for the American College of Emergency Medicine's Third Performance Measures and Benchmarking Summit. The purpose of the summit was to build upon the results of previous summits to improve the timeliness and efficiency of emergency medical care.

The summit participants concluded that "Variation is at the root of all quality issues. Whether found in a highly mechanical production environment or consumer-oriented service industry, variation invariably precedes system failure." 7

The researchers went on to say, "Measurement is the most fundamental tool in the hospital leader's toolkit to identify and mitigate [practice] variation." 7

In our practice, we have noted two front-end emergency operational activities prone to wide variation due to human subjectivity:

1) Emergency Severity Index (ESI) designations, and

2) Medical screening exams (MSE).

It has only been 18 years since two emergency room physicians, Drs. Richard Wuertz and David Eitel, developed the original ESI five-level patient triaging concept in 1998. However, the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) designations did not become fully adopted until around 2010 with the introduction of online CEU-credited ESI courses, enabling widespread access to training. 8

While seven years seems like an eternity in our fast-paced world, the reality is even with availability of online training, ED physicians and nurses around the country are still not consistently coding and stratifying patients in exactly the same way. The ESI system, though far superior to no system at all, is still hampered by human subjectivity. This is why the American College of Emergency Medicine's Third Performance Measures and Benchmarking Summit was so important.

If you are not tracking and trending and reviewing weekly the breakdown of your ED's ESI scores to determine statistical variation between providers, you are likely to find that your organization is vulnerable to legal risks. Consumer demand for transparency is greater than ever. The absence of consistency in designating appropriate ESI levels creates havoc downstream, including impeding patient throughput.

Conclusion:

The main point of reviewing how your ED uses technology and staff and tracks and trends clinical patient outcomes is to provide seamless and effective emergency care. Seconds and minutes save lives. If you haven't taken a deep-dive into your ED operations lately, maybe you should.

The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, Inc., its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals.

Pamela Froneberger is a Director at FTI Consulting and is based in Charlotte, North Carolina. She is part of the Health Solutions segment. Pamela's 30 years of clinical and operational healthcare experience have focused on clinical, financial and operational improvements in a variety of healthcare settings including multi-state IDNs, urban academic teaching hospitals, rural and critical access hospitals as well as non-acute healthcare providers.

Prior to working with FTI, Ms. Froneberger held various cardiovascular clinical nursing, supply chain management and clinical performance improvement positions with a national group purchasing organization and a Fortune 500 cardiovascular medical device company. Ms. Froneberger is a fellow and certified healthcare resource manager through the American Society of Healthcare Resource Management. She has published healthcare operational improvement and physician engagement articles in Becker's Hospital Review, Physician Executive, Cath Lab Digest and other national healthcare journals.

Ms. Froneberger received her B.S in Nursing from The University of North Carolina-Greensboro and completed post-graduate Healthcare Executive Fellowship Program in Management from Northwestern University's, J.L. Kellogg Graduate School of Business.

FOOTNOTES:

1: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center of Health Statistics, Emergency Department Stats, January 17, 2017.

2. Repeal of Obamacare could put strain on local ERs, affect contraceptive benefits, by Brie Zeltner, The Plain Dealer November 11, 2016.

3. International Journal of Emergency Medicine (IJEM), "Health information technology in US emergency departments", September 3, 2010, Daniel J. Pallin, et al.

4. Journal of Emergency Medicine, "Adoption of Information Technology in Massachusetts Emergency Departments, February 18, 2009, Daniel J. Pallin, et al.

5. Becker's Hospital Review, "7 Innovations Transforming Emergency Care", by Regan Henry, PhD, AIA, LEED AP, LSSBB, February 13, 2017.

6. American College Emergency Physicians News, "Staffing an ED Appropriately and Efficiently", August 2009 by Martha Collins.

7. Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, "Emergency Department Performance Measurement Updates: Proceedings of the 2014 Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance Consensus Summit, April 21, 2015 by Jennifer L. Wiler, MD, et al.

8. Emergency Severity Index (ESI): A Triage Tool for Emergency Department. Content last reviewed February 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD.

The views, opinions and positions expressed within these guest posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of Becker's Hospital Review/Becker's Healthcare. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.