If you are going fishing it makes sense to fish where the fish are.

Biomedical research in academic medical centers and hospitals have long been sources of institutional pride as they help attract physician specialists while burnishing an institution's reputation in targeted centers of excelle

nce.

Supporting research is also an expensive proposition. During the heyday of NIH, there was enough funding and high indirect cost coverage to justify the construction of grand research facilities and the hiring of expert researchers. But those days are over and are not likely to return anytime soon. If passed, President Obama's proposed one billion dollar budget increase would mark only the third time since FY2003 that the NIH budget increased more than the cost of research. In 12 of the past 13 years, this funding has either been cut or has failed to outpace rising costs. Today, in constant dollars, the NIH budget is more than 22 percent below the FY 2003 level.1

While sequestration was temporarily suspended in FY 2014 and 2015, it could return in 2016 and beyond, and would reduce the federal budget by 8.2 percent, as directed by provisions in the Budget Control Act. Applied to NIH, a reduction of this size would not only wipe out any small increases in funding, it would require catastrophic cuts to ongoing research grants while stifling new projects. For the NIH portfolio, 8.2 percent represents over one-half of the total funding for new and competing renewal research grants.

Can hospitals afford to grow their research enterprise...or maintain it at current levels? If you look at the fundraising enterprises at our nation's leading healthcare research institutions, you'll find well over half of the funds raised are for support of research. Hundreds of millions of dollars are raised to support research, to enable innovation, or to fill budget gaps for retaining researchers who did not receive NIH funding. In these scenarios, philanthropy does not contribute to the bottom line of the hospital. In fact, most of these outstanding fundraising programs do not raise enough unrestricted gifts to cover their own fundraising expenses. From a CFO's point of view, the fundraising program is costing the institution money, even when hundreds of millions of dollars are secured for research.

It is time for hospitals and healthcare research institutions to target a portion of their philanthropy resources for population health research leading to population health programs. Now that the payer model is changing to reward ACOs and other models designed to keep people healthy, this will bring more money to the bottom line.

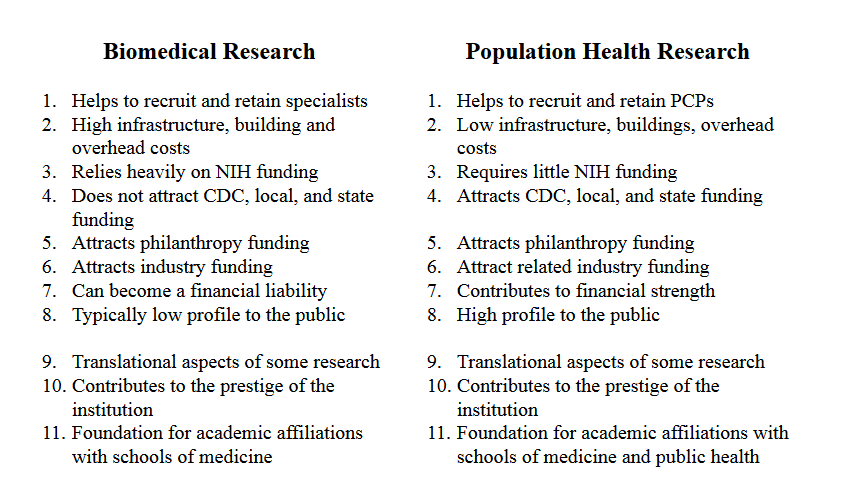

When comparing the merits of each approach, we see important similarities and differences in generating institutional viability.

Because population health and ACO funding are becoming a big fish in the healthcare industry funding pool, the industry needs to revisit its "sacred cows" and examine its philanthropic priorities during this time of profound change.

Larry G. Raff, MPH, is president and principal of Copley Raff, Inc., a leading philanthropy consulting firm based near Boston. He brings three decades of leadership and experience to healthcare organizations seeking advancement results. His clients include four of New England's largest multi-hospital systems, the largest multi-hospital systems in the Midwest and South Florida, numerous academic medical centers and community health centers. He also provides counsel on ACO fundraising strategies.

________

1 Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology

The views, opinions and positions expressed within these guest posts are those of the author alone and do not represent those of Becker's Hospital Review/Becker's Healthcare. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them.