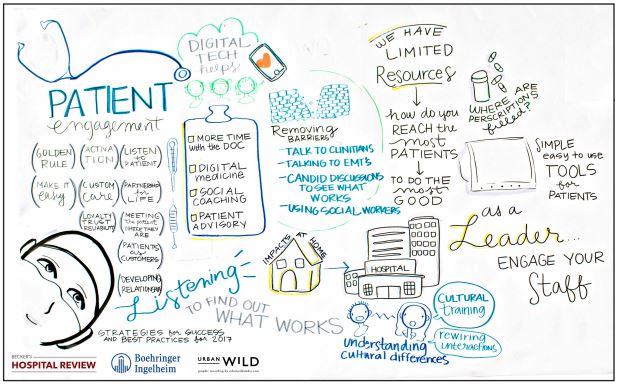

In April, 32 executives, vice presidents, directors and other senior-level healthcare professionals gathered in Chicago to share insights and explore solutions to the industry's most pressing challenges, including patient engagement, quality improvement, system integration, clinician wellbeing and the relationship between these critical priorities. This live discussion was captured in a graphic recording, pictured below.

Leaders' dynamic discussion has been captured in a three-part series: Part I (Patient engagement), Part II (Care quality improvement in times of value-based care) and Part III (Functioning as a system).

We are pleased to share Part I in this issue; to see how the conversation unfolds, follow the series in subsequent articles.

This meeting and article were paid for through a sponsorship by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals.

Patient engagement

When 13 healthcare leaders were asked to define "patient engagement," it didn't take long for common themes to emerge in their answers. Each of these healthcare leaders possessed a clear vision of what patient or consumer engagement looks like in his or her organization. The idea of partnership was by far the most pervasive notion to emerge.

"Engagement means we are partners for life — listening, educating and coming to an agreement on a plan," said the COO and CNO of a 191-bed suburban hospital in the Midwest.

Although leaders shared a common vision of engagement, they noted caveats or nuances when defining it. For one, there is still room for debate around using the terms "customer" or "consumer" interchangeably with "patient." Such traditional business lexicon does not easily roll off the tongue for all hospital executives or clinicians. Although a growing number of healthcare professionals do use the term "consumer" or acknowledge consumerism influencing their work, the term is not yet universally accepted.

Another caveat to keep in mind, according to leaders: Patient engagement looks or feels different depending on the condition, acuity of illness, age or patient disposition.

Consider how the needs range between a patient with type 2 diabetes, one with stage 3 colon cancer or another with a rare disease. As for age, the president of a major children's hospital in the Southeast said his teams are tasked daily to build engagement with both patients and entire families. "Children have very unique needs," he said. "Their emotional contents are different, and most parents feel when something happens to their kids it's much worse than anything that could happen to them."

But perhaps the largest caveat noted was the dilemma hospitals face to engage patients in a sustainable way in light of restricted resources, be it talent, finances or time.

"Ideally we want to follow-up with 100 percent of patients," said the vice president of outpatient pharmacy for a 48-hospital system in the Southwest. "The reality is we have limited resources. We can only touch the ... 20 percent [with the greatest needs], most of whom account for 80 to 85 percent of our spend. It's a challenge every system is facing: How do you utilize the limited resources to do the best you can?"

With these qualifications in mind, the conversation turned to effective strategies health systems are deploying to build and sustain partnerships with patients. Here are key takeaways from the discussion.

The power of radical candor from patients

When asked to define patient engagement, one executive put it succinctly: "We need to start listening to them." In the dialogue that followed, she and her colleagues illustrated a variety of ways in which care teams are doing just that.

The first method is tried and true: patient advisory boards. In the past five years, a growing number of hospitals and health systems have recruited patients and their families to serve on governing bodies that work alongside hospital staff and leadership to influence policies, programs and protocol. Several conversation participants said they see meaningful results and input from these trusted advisories.

"Our patient advisory group is extremely engaged and active," said the vice president of quality management at a 245-bed hospital in the Northeast. The group was established seven years ago and sees a lot of community involvement. "They want our hospital to stay as their community hospital, even though we are now part of a larger system."

Another aspect of patient engagement that emerged was helping patients become active participants in their own health, and act as partners with their physicians in making healthcare decisions. "If patients are not actively taking care of themselves, they won't have good outcomes, so it's about making sure you meet the patients where they are," said the chief diversity officer at an international organization. "Patient engagement is also about understanding the socioeconomic components [of a patient's condition]," she said.

Healthcare leaders agreed this version of patient engagement requires providers to approach care management holistically rather than episodically, as they have in the past. Leaders said their organizations are finding new ways of getting patients engaged in managing their health between checkups. The CNO of a 240-bed hospital in the Midwest said her nurse navigators are now expected to engage readmitted patients in conversation and investigate the social, economic or demographic factors that could be responsible for their readmission.

To learn this, nurse navigators ask patients a series of questions. "Did we not give them enough information? Do they not have the resources to get what they need?" asked the CNO. "Did we not help them understand how important it is to follow-up on the things we asked you to do? That's what we're doing differently to help us engage with our patients to understand what failed."

These straightforward, one-on-one conversations have yielded powerful qualitative data and narratives for care teams to address specific patient needs. Previously, using clinical data or close-ended questionnaires, clinicians had difficulty identifying core reasons for a patient's readmission. Sometimes the trigger for readmission is not found in an EHR or spreadsheet, as these discussions have shown.

"We had a patient readmitted with out-of-control diabetes," said the CNO. "We were trying to figure out why she was not taking her insulin. She was taking it, but she didn't have a refrigerator to store it in because it broke."

Armed with this new information, and knowing that the temperature of insulin influences its efficacy, the hospital bought the patient a new refrigerator to safely store her medication. Afterward, she only arrived to the hospital for scheduled appointments versus ER visits or readmission.

Time to challenge the status quo

Healthcare is a highly regulated industry rife with red tape, protocol and policy. Yet to better engage patients, several executives underscored the need for care teams to challenge the rules.

The example of a hospital purchasing a patient a refrigerator is one example of an unconventional action that resulted in big benefits for both the patient and hospital. Leaders said patients have a lot to gain when healthcare professionals are encouraged to think creatively and question the way things are "always" done.

"We have a lot of processes set up because that's the way it's been for a really long time," said the vice president of nursing and patient care at a 34-bed rural hospital in the Midwest. "It's time to take a step back and say, 'Well, why do we have that in place? How can we break it so it works better for this patient?' Removing those barriers helps the patient see what you've done and become more involved."

Some organizations are working to make "unconventional thinking" a key part of how the system approaches patient care. For example, one hospital executive said his system is working to create advisory groups of families — but with a loose interpretation of the term. "Not just the family as you see it, but as the patient sees it — which could be their neighbors or friends. It's more about the customer: Who is their family?"

Executives also emphasized the need to challenge their own assumptions and view each patient as an individual with unique fears, preferences and needs.

"It's about shifting the way we as healthcare providers or a healthcare system view the patient and disease," said the vice president of quality management at a 245-bed hospital in the Northeast. "We're so used to it. We hear it and see it every day. But it's new for this person — it's important to remember that even though we've been practicing for 20, 30 or 40 years, it's new for them. It's a game-changer."

Empower care teams with multicultural education and awareness

Many leaders are encouraging their teams to challenge assumptions while also building a stronger understanding of their multicultural communities. Cultural competency was an important theme of the conversation that took place between the 13 healthcare leaders.

Several noted how, for years, hospitals have operated on cultural assumptions or were oblivious to how routine offerings or interactions were perceived by individuals from diverse backgrounds. This includes everything from a physician greeting a patient on a first-name basis, to offering ice chips as fluids for hydration, to assuming heterosexuality on paperwork or questionnaires offered at OB-GYN appointments. In certain cultures, the lack of a courtesy title is perceived as rude, fluids are preferred at room temperature and suppressing one's sexual orientation is an offensive breach of patient-provider trust and a contributing factor to inadequate medical care.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to build engagement among patients if hospitals and healthcare providers do not embrace and respond to cultural and demographic differences. The senior vice president of pharmacy services for a 15-hospital system in the Southeast said his organization has a chief diversity and inclusion officer, and it also taps advice and perspectives from "business resource groups."

Similar in function to patient advisory boards, these business resource groups are made up of volunteers from the community who organize based on shared race or ethnicity. "We run our patient-centric care models through those business resource groups to truly segment the populations to make sure we're delivering the care in a way that meets people where they are," said the senior vice president.

Leaders agreed: Teaching clinicians about multicultural awareness is valuable to their organization. However, limited resources and physician time make implementing these initiatives challenging, they said. As is, patient-provider interactions already take a great deal of emotional intelligence, and properly addressing the nuances or subtleties of multicultural relationships can be a challenge.

"Navigating those situations is extremely difficult," said the CEO of a 429-bed children's hospital in the Midwest. He said it is one of the less explored aspects of medicine. "These are profound differences. I had to completely rewire my conversation style when I moved north. We have to decide what kind of society we are. If we continue to be a multicultural society, it will be critical to understand the fundamental differences between us."

The September and October issues of Becker's Hospital Review will feature Part II and III of the conversation, which focus on quality improvement, value-based care and system integration.